Weight gain worries for newer HIV treatment regimens

But these medicines are well tolerated by patients

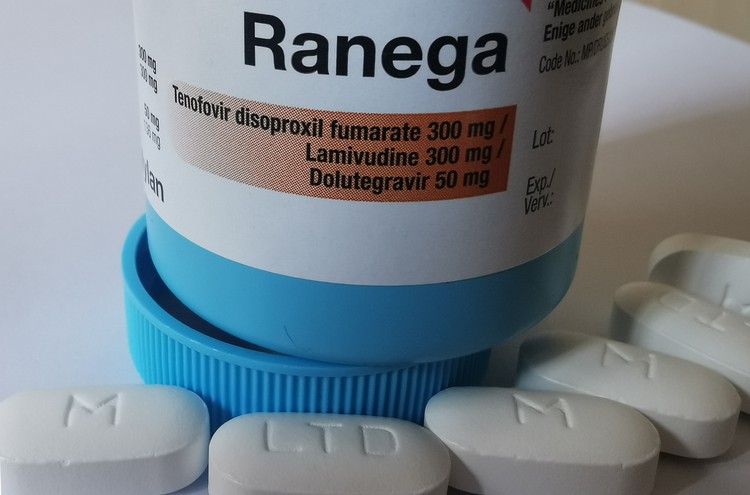

This is the HIV combination treatment pill of choice (though this is only one of several brands) for newly diagnosed HIV patients in South Africa. The regimen has proven very effective at suppressing HIV, and patients tolerate it well, but it is associated with obesity in women.

- A South African study has found that a substantial number of women with HIV become obese on newer antiretroviral drug regimens.

- One of the drug regimens tested in the trial is almost identical to the first-choice regimen used in the public health system.

- HIV became undetectable in most patients in the study, which is a desirable result.

- Patients also tolerated the medicines well.

- Nevertheless the high level of obesity is a health concern.

- The study, published in The Lancet HIV on Thursday, shows the importance of local HIV drug trials.

A new study led by Ezintsha, a University of the Witwatersrand-based HIV treatment research group, has revealed that newer antiretroviral (ARV) treatment regimens lead to worryingly high levels of weight gain, particularly in women.

In the early days of the HIV pandemic, many people with the infection wasted away, unable to absorb their food properly. Today, with ARV treatment for the disease being so effective, this should never be a concern. Ironically, with the newest ARV regimens, the opposite problem has arisen: some patients are picking up an unhealthy amount of weight. And although this is a far better situation than your body literally starving, it is still a troubling health concern.

The results of the study, called ADVANCE, are published on Thursday in the Lancet HIV journal. Over 1,000 people living in central Johannesburg were enrolled in the 96-week long trial, which investigated the long-term effects of three different HIV treatment regimens, including South Africa’s current standard combination prescribed to new HIV patients.

According to the authors of the study, “little research has been done on African populations” using these regimens until now, owing to the drugs’ development in western laboratories using largely western populations. The study finds that a newly introduced treatment combination produces high rates of clinical obesity, in women in particular.

The three regimens examined in the study were:

- Tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF), emtricitabine (FTC) and dolutegravir (DTG);

- Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), emtricitabine (FTC), and dolutegravir (DTG); and,

- Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), emtricitabine (FTC) and efavirenz (EFV).

The ADVANCE study found that 28% of women on the TAF/FTC/DTG combination became obese. By comparison 18% of women on the TDF/FTC/DTG combination became obese, and 12% of women on TDF/FTC/EFV. The women were not obese at the time of the commencement of the study.

Obesity is a public health concern in South Africa, leading to a number of associated health problems, from diabetes to heart disease. 41% of adult women in South Africa are obese, while 11% of men are obese, according to data from the 2016 South Africa Demographic Health Survey. Obesity is defined as a body mass index greater than or equal to 30 kilograms per metre of height squared (see Wikipedia for details).

In November 2019, Health Minister Zweli Mkhize announced the launch of the new antiretroviral regimen, known as TLD. This regimen combines TDF, lamivudine (3TC), and DTG, but FTC and 3TC are interchangeable, so it is practically equivalent to the TDF/FTC/DTG regimen associated with 18% of women becoming obese in the study.

Regimens that use DTG have been widely hailed as a huge advance in the treatment of HIV. DTG blocks HIV from integrating with the DNA in the cells. It works rapidly to reduce viral loads, has shown fewer side effects than previously-favoured drugs, combines well with other medicines, results in much less drug resistance in patients, and is cheap to produce. The drug that DTG largely replaced in treatment combinations, EFV, is significantly less capable in these respects.

TAF has been positioned to replace TDF, according to the 2020 Clinton Health Access Initiative HIV Market Report. TDF is used by about 94% of patients in 2020.

While weight gain in patients with HIV has been a signal of a return to health, the ADVANCE study argues that “the sustained increase, including in individuals with higher CD4 counts and with a strong sex difference, and the substantial differences in weight gain between the two DTG-containing groups, suggests other factors are involved.” Other antiretrovirals are not associated with such large weight gain.

A 2020 paper in the Journal of Virus Eradication, whose co-authors include a number of researchers responsible for the ADVANCE study, criticised the manner in which Phase 3 trials (the large study in humans before a drug is approved) of antiretrovirals are conducted. While white men make up only 6% of the global HIV epidemic, they constitute 51% of subjects in phase 3 trials. Black women constitute 41% of the total HIV prevalence world-wide, and yet made up only 7% of the population in the DTG phase 3 trials examined. The current practice, in which trials are run in Africa only after testing has finished in high-income countries, “leads to delays in our understanding of drug safety”.

Despite the weight gain, patients using any of these treatments are far better off than not being on treatment or the earlier ARV combinations. In all three regimens the amount of HIV in the vast majority of patients was reduced so much that it became undetectable.

“Make no mistake: this is a step forward for antiretroviral therapy,” Professor Francois Venter, the principal investigator on the trial, told GroundUp. “The recommended treatment is good in South Africa, but we will need something else for people who are gaining weight; it’s an urgent research priority.”

Next: Late judgments: Is the Cape High Court doing better?

Previous: Covid-19 has made inequality worse, researchers find

© 2020 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.