Social grants falling as share of state expenditure

Yet percentage of people living in poverty has grown

The proportion of state spending on social grants is falling in the face of a desperate need for social assistance.

Section 27(1)(c) of the Constitution provides guarantees against income poverty for all people living in South Africa through the right to social security.

But according to Statistics South Africa, income poverty has been rising consistently since 2011. Using the StatsSA poverty lines which are updated each year to keep pace with inflation, in 2011, 53.2% of people were living below the poverty line of R992 per person per month. In 2015, this had risen to 55.5% of South Africans – more than one in every two people. Also, more than one in four people in South Africa were permanently “food poor”. They did not have enough food to provide for their daily needs (let alone other needs like housing, water and transport).

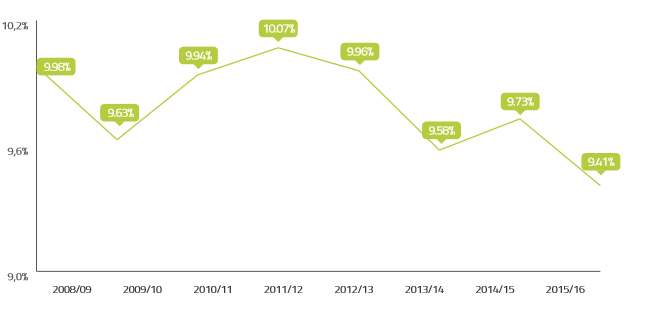

Yet the proportion of the total consolidation spending of the state (municipalities, provinces and national government) allocated to social grants has been falling, as the graph below shows. From 9.8% in the 2008-9 fiscal year, spending on grants rose to over 10% in 2011-12, but has fallen to 9.41% in 2015/16 - lower than the 2008 figure.

Social grants were listed in the 2015 General Household Survey of StatsSA as being the primary source of income for 21.7% of households in South Africa, and a contributing source of income for close to half (46.2%) of households in South Africa. Incomes from salaries were only received by 65.5% of households in South Africa in 2015.

Social grants are clearly a critical source of income to households: but are they enough?

Social grants are targeted at categories of people historically excluded from the labour market - children, older people and people living with disabilities - and are conditional. Children have to attend school to get the grant. Grants are means tested. Despite a national unemployment rate (including people who have given up looking for a job) of 36% of working age people, there is no social grant for poor, able-bodied working age people. Targeted assistance to grant recipients is diluted among the rest of the household.

The bulk of the social grant transfers received are Child Support Grants. These made up just over 12 million of the 17.2 million grant recipients in 2017. In 2017 the StatsSA Food Poverty Line - the minimum needed to afford enough food to survive - is R531 per person per month. But the Child Support Grant is R380 per person per month. This is only 71.5 % of the monetary value necessary to keep each child alive. And the proportion is falling: in 2015, the grant made up 73% of the Food Poverty Line.

Cash grants are an important policy tool for a number of reasons. They prevent people from dying of hunger. They enable the state to assist in meeting people’s needs without having to grasp the nettle of redistribution of wealth, which is clearly not something for which there is currently much political will. Yet despite the obvious need for assistance, the Department of Social Development reported a reduction in the number of Child Support Grant beneficiaries in the current fiscal year. This, the department said, was due to a “lower than expected” uptake, a reduction in the Disability Grant as a result of fewer “fraudulent claims”, and a reduction in the number of Care Dependency Grants (for disabled children) as a result of gaps in legislation that rendered the definition of a disabled child difficult.

The National Treasury has budgeted for current grant coverage to keep pace with inflation. This means there will be no real increase in the value of grants (the goods and services the grants can buy) and so no progress for beneficiaries towards a better standard of living. It is also curious that there has been no action on getting rid of the financial means test for the Child Support Grant or the Old Age Pension, despite two draft discussion papers having been finalised on this, according to the 2015/16 annual report of the department of social development.

Social grants are providing much needed, although highly inadequate, income for very poor people, and many would argue that social grant allocations need to grow, and certainly not shrink.

Views expressed are not necessarily those of GroundUp.

Next: Lufthansa named in irregular PRASA contract

Previous: Failure of commuter rail is a crime against urban poor

Letters

Dear Editor

The argument that social grants expenditure must increase is made baldly without consideration for the country's exigent fiscal and macro-economic situation – debt as a percentage of GDP 52%; revenue shortfall of R50bn; growth at a moribund 0.6% and 20-year flat 3.5% and so on.

Under these circumstances, how can allocations grow? Please, Ms Frye, make realistic suggestions.

Already grant and public sector salary expenditure combined are the largest budgetary items and the primary cause of the large government debt. Already 17 million people, a third of the population, receive grants. If the quantum of individual grants and allocations are expanded to new classes of beneficiaries, how will this be paid for? Is it Frye’s argument there should be no cap on any of those?

Social workers see its value in terms of the benefit to the individual but economists and treasury accountants ask “How shall it be paid for?”, the same scenario government faces with the unrealistic call or free university fees. But at least proposals for how to fund it were made.

I’m sympathetic to the notion of grants – we know a family of five who live from hand to mouth from three childcare grants and whatever they can scrounge. But social transfers do nothing to enable people to acquire and develop livelihood assets; it entrenches long-term poverty and helplessness and creates the conditions for entitlement, which in South Africa is a huge problem on its own. It must be viewed as an emergency measure, and then only for the truly vulnerable.

Arguments like Frye’s are undermined when it presents the socio-economic milieu in stark, binary terms – grants or no grants – without exploring those fiscal and macro-economic issues I mentioned. And there’s no excuse because her organisation has the resources – as has anyone with access to the Internet – to review the fiscal and economic reality.

© 2017 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.