Premier’s excuses leave the lights off

Last week GroundUp and the Cape Times published Doron Isaacs’s detailed account of his repeated but unsuccessful attempts to have authorities repair dysfunctional streetlights in Khayelitsha.

For six months, Isaacs has been in regular contact with Western Cape Premier Helen Zille on Twitter, a medium through which she has developed a reputation for promptly responding to service delivery complaints. Despite several public commitments from Zille (as well as Cape Town Mayor Patricia de Lille) to address this, much of Lansdowne Road, one of Cape Town’s busiest thoroughfares, remains in darkness. No apology or plan to remedy the situation have been issued.

It is worth taking a moment to reflect on the impact of inadequate street lighting in townships. Residents must routinely walk very long distances at night or in the early morning to access public transport to get to and from their places of work. Similarly, residents must often travel on foot for hundreds of metres or even kilometres to relieve themselves in communal toilets or open clearings. These and other activities often involve crossing or walking along busy streets like Lansdowne Road. There are frequent reports of pedestrians being hit by vehicles in the process of doing so. Conducting basic activities that some take for granted costs many Khayelitsha residents their lives.

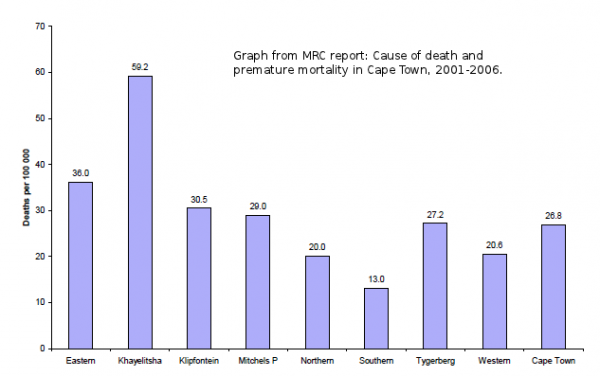

Western Cape Transport MEC Robin Carlisle recently acknowledged that in 2011, 648 (49%) of the 1321 people who died on the Province’s roads were pedestrians. This is an 8% increase in the proportion of pedestrians killed since 2009. He noted that the majority of these deaths were in “poorer communities”. This claim is supported by a 2008 study published by the South African Medical Research Council in collaboration with the City of Cape Town, which found that one is twice as likely to be killed in a road accident in Khayelitsha than in Cape Town’s CBD and almost five times more likely than in the southern suburbs(http://www.mrc.ac.za/bod/premort_cpt.pdf). Children are particularly vulnerable. According to a World Health Organisation report, pedestrian accidents ranked as the top fatal injury for children between 0 to 14 years in Cape Town, accounting for just under 50% of all fatal injuries for that age group.

There are of course many other factors contributing to pedestrian injuries, including alcohol abuse, but studies have shown that street lighting can through a range of technologies (including sustainable ones like solar powered) effectively and dramatically reduce incidence of pedestrian mortality.

Walking long distances in darkness also increases vulnerability to crime. This is particularly true in Khayelitsha, which has one of the highest crime rates in the country. The City and Provincial Government have lauded the positive impact of public lighting on crime reduction, most notably by investing heavily in the Violence Prevention through Urban Upgrading (VPUU) project.

The primary response from both the Province and City has been to claim that a lack of functional street lighting in Khayelitsha is primarily due to vandalism, despite the fact that much of Lansdowne Road has no street lights at all. This argument is adhered to religiously when accounting for poor service delivery in townships, including for other basic services like sanitation. In an attempt to absolve government of accepting responsibility for its own failures it ignores a host of other factors that deserve equal if not more attention.

On Monday, in response to a query as to whether any action has been taken to remedy the lack of street lights, Premier Zille claimed, “Communities MUST take ownership of infrastructure.” Khayelitsha is home to between 500,000 and 750,000 people. Many of these residents must make use of the township’s roads, communal toilets and other public goods. The vast majority of these residents behave within the confines of the law, and are in effect being collectively punished for the actions of a few.

So-called “illegal” electricity connections are a challenge that must be overcome, but it is a reality forged out of desperation and not criminality, in need of a coordinated and compassionate response.

Where genuine vandalism occurs, particularly when it jeopardises an essential service, government is legally obligated to take appropriate steps to prevent it. This has been done in many other areas. When the N2 was blocked during service delivery protests late last year, additional Metro Police vehicles were parked alongside the highway around the clock to monitor the situation for more than a month. The installation of more than 100 CCTV cameras in the inner city has resulted in significant reductions in vandalism and crime. This is why government exists—to take action where the “community” cannot. It is legally and morally obligated to find solutions.

In addition to addressing vandalism, government must look closer to home. A significant culprit of failing services is inadequate government maintenance and monitoring of amenities in townships. Despite repeated claims by the City that vandalism accounts for most sanitation related faults, a recent baseline survey conducted in Khayelitsha by the City found that only 20% of these faults was due to vandalism, while the remaining 80% was due to overuse and poor maintenance. The mere fact that Lansdowne Road has been in darkness for more than six months proves that at best the City is failing to monitor and repair basic services, and at worst that they are aware of the problem but have chosen not to fix it.

Lansdowne Road could well serve as the de facto border between Cape Town’s historically neglected and privileged areas. The suburbs to the north and those to its south continue to receive vastly different qualities of service, a fact that Mayor Patricia de Lille has acknowledged. Few would argue that streetlights would be allowed to remain dysfunctional in Bellville or Rondebosch or the City Centre for a week, let alone six months. There is a lot that must be done to address these inequities. A good place to start would be for government to accept responsibility and respond accordingly, instead of blaming those who have suffered as a result of the state’s failure to meet its constitutional obligations.

Gavin Silber is Policy Coordinator of the Social Justice Coalition. You can follow him on Twitter @GavinSilber.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.