I’ve been raped. What do I do now?

“There are so many things that rapists and communities do that feed myths and false notions about rape,” says Rape Crisis director Kathleen Dey.

“Rape survivors are often shamed into thinking that they were somehow asking for it,” she says.

South Africa has a high incidence of reported rape: 46,200 rape cases were recorded in the 2013/14 police statistics (see page 19). However, the Medical Research Council estimates that only one in nine rapes are reported to authorities.

What is rape? Can husbands rape their wives?

“Rape is being forced to have sex without your consent. It’s a violent crime,” Dey explains. She says many people still believe that a wife can’t be raped by her husband. “This is rape, but it’s considered a norm so that people, especially older people, wouldn’t consider it rape,” she says.

Dey said that another myth that needed to be addressed was often fueled by the police. “When someone is raped when they are drunk, they are often shamed into thinking that they were somehow asking for it,” Dey says. But she points out that people who are drunk are not able to give consent, so police should not dismiss women who say they were raped while drunk.

What to do if you’ve been raped?

Rape is a violent and traumatic crime that often leaves physical and emotional scarring. While the incident may be extremely overwhelming, it is important to get help and immediate medical care where needed.

Rape Crisis recommends you do the following If you’ve been raped:

Get to a safe place as soon as possible.

Call for help and tell someone you can trust about the incident.

“It’s very important that you tell that person everything that happened to you. It can be a stranger or someone close to you. Should you choose to open a case and it goes to trial, this person can be called to testify and corroborate your story,” Dey says.

Don’t wash or throw your clothes away as there might be hair, blood or semen belonging to the rapist that can be used as evidence if you decide to report the incident to police.

“You can have evidence collected and choose not to report the rape. You will have a month to change your mind because after one month the health facility will destroy the evidence,” Dey explains.

If you’ve been physically injured, go straight to the nearest hospital or clinic for treatment. The staff will contact police should you request it.

If you are not injured, but severely traumatised try to find someone you trust that can go with you to the police station nearest to where the rape took place. There you should be assisted by a member of police’s Family Violence, Child Protection and Sexual Offences (FCS) unit.

“The person will be taken to one of several designated facilities in the province for treatment or a medical examination with a rape kit. It’s important to have someone with you if possible throughout this process,” Dey says.

At the hospital, every part of your body will be examined to find and collect as many DNA samples as they can find. Any DNA found will be sent to a laboratory to be analysed and a police docket opened should you choose to report the rape.

Make sure the doctor or nurse gives you the Morning After Pill if the rape occurred within a 72 hour period of the medical exam. You should also be tested for sexually transmitted infections including HIV. If you are HIV-negative, and it is within 72 hours of being raped, you can ask for antiretroviral medicines, which you will need to take for a month. This will reduce the risk of contracting HIV.

Once you’ve had the medical exam, you can wash and change clothing, but don’t throw your clothes away.

Kathleen Dey, director of Rape Crisis. Photo courtesy of Rape Crisis.

Kathleen Dey, director of Rape Crisis. Photo courtesy of Rape Crisis.

Reporting rape

Dey said men who have been raped are often more reluctant to attend counselling than women.

“We find that while men report the rape because they’re keen on getting justice, but they often turn their backs on the rest of the process. About one percent of the men we see at hospitals make it through to our counselling centres. Men are the victims of about 10% of rapes,” she says.

When you report a rape:

An FCS Unit member will take down your statement. If you don’t want to go to the police station, you can request for an officer to be sent to your house, but this may take longer.

Read through the statement and only sign it if you agree with everything in it.

If you know the perpetrator, he will be arrested as a possible suspect and the matter will go to court for hearing.

“Sadly, if the survivor doesn’t know his/her rapist, the case often ends at this point,” Dey says.

Rape Crisis has volunteers at five regional courts that will help you understand the court process and prepare you for what can be expected during the hearing. “This process can be terrifying for most people, especially if you are grilled by the defence about your testimony,” Dey says.

Should the person be convicted, they could be imprisoned for a minimum period of ten years, but he might receive parole earlier.

“We advise survivors to find out which correctional facility the rapist will be held and ask the facility’s parole board to notify you when the person is offered parole,” Dey says.

Counselling

Rape Crisis has offices in Observatory, Khayelitsha and Athlone.

“We’ve got people from Khayelitsha that would rather travel all the way to our Observatory office for counselling. If you don’t want anyone to know, you will try to get help as far from your home as possible,” Dey says.

She says it is important not to force a survivor into counselling soon after the crime, if he or she is not ready. “I recommend that the family of a rape survivor gets counselling. They will be the people who need to understand why the survivor may not want to talk about the incident immediately or how to support them once they do decide to talk about it.”

“All of our counselling is done by volunteers we’ve trained in the community. When you come to us, you can speak to someone who understands where you come from, speaks your language and may understand your religious beliefs,” Dey says.

For more information vist the Rape Crisis website or call the 24 hour helpline based in Observatory on (021) 447 9762 from 9am to 5pm. Contact the Khayelitsha counselling centre on 021 361 9085 or Athlone on (021) 633 9229.

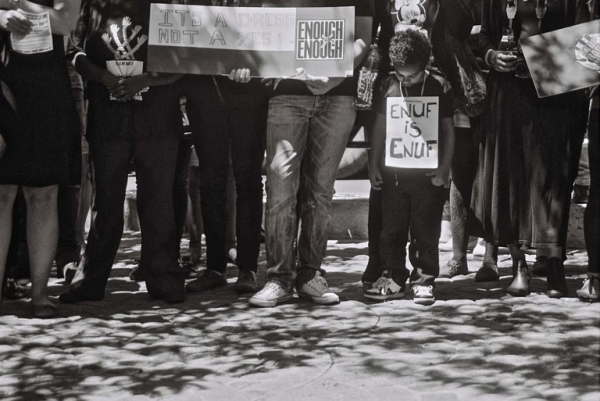

Next: We shouldn’t have to apply to protest, say activists

Previous: Art in a Khayelitsha fruit & veg shack

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.