27 May 2014

They fight to kill - with pangas, knives and their bare hands. They don’t know why the fighting began but it doesn’t seem to matter. Proving your manhood doesn’t require a reason.

And in Khayelitsha, where the teenage Vato and Vura gangs battle for control of the potholed streets, the body count rises almost daily. High on tik and magic potions from sangomas, these youngsters rule the schools and terrorise any adults who stand in their way. Armed taxi drivers used to have a measure of control, firing over the heads of warring gangsters, but not anymore.

“People didn’t have faith in the police so they’d call us,” a taxi driver said. “We used to beat them to make them stop. But we don’t any more because these youngsters have become very dangerous - possessed, really. They live in our neighborhoods and we can become targets.”

Unlike coloured gangs, who usually battle with guns over drug turf, the Vuras and Vatos appear to be influenced by traditional stick fighting in the rural areas from where they, or their parents, often originate. A gang member pointed out that using pangas, sticks and knives was more manly than using guns. “We want to feel an achievement when we beat our enemy,” he said. “Guns have power but give no satisfaction.” Another gang member pointed out that they don’t use guns because they don’t have access to them. So they use whatever sharp weapon they can find, from a pencil to a panga.

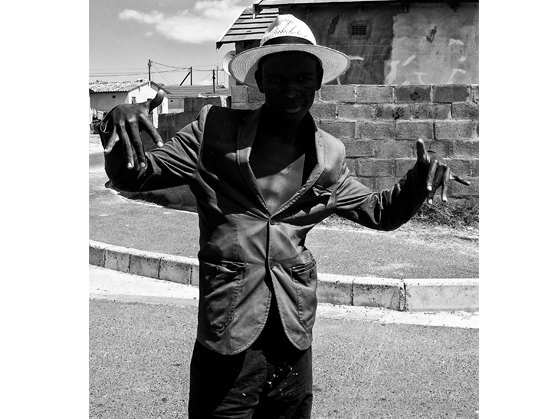

Acting adult: this is the handsign of the 28 prison gang.

One Friday afternoon, I was standing near a bridge in Site B, Khayelitsha, when tension rippled through pedestrians, who fled from the bridge in near panic. Under the bridge, I saw a group of armed youths, many in school uniforms with satchels on their backs. Another group of about 25 to 30 youngsters swarmed towards them and a fight, involving stones, knives and pangas, began. It was almost theatrical. Each person appeared to have a particular target in the opposing group. As I watched, two gang members were cornered and beaten with stones. One was stabbed in the head. The fight stopped when a taxi driver began shooting over the youths’ heads. They dispersed, assisting the injured.

Andiswa, a pupil who lives near the bridge, told me she watches the fights from her house and finds them interesting. “They usually fight on Fridays,” she said. “Sometimes they run right past here. It’s exciting.” While battles are more formal, flash attacks can happen at any time. Young people are always on the alert and aware of whose territory they’re in. It’s a stressful existence. Gang members use hand signals and a gang language called gurantsa to identify each other. They use special whistles to coordinate an attack.

High on tik and adrenaline, gang members have hair-trigger moods and are totally unpredictable. A gang member bragged to me about an attack that left a teenager dead: “There were 14 of us and there were three of them. Two ran away, but we wanted to make sure that those two who ran would get the message not to mess with us. We beat the [remaining] guy and stoned him. Someone took a brick and smashed his face until he was dead. We left him there.”

T-boss was arrested a year ago and charged with the murder of a 15-year-old boy. He was in prison for six months but, he said, the charge sheet “went missing” because “I bring business and know things that can get people in trouble.” When asked to elaborate he said it was a “private matter”.

T-BOSS explained that the fights started years ago. “One of the boys from Graceland was stabbed to death at a pub in F Section. So we made sure we were going to have revenge and we did. As years passed people had other reasons for fighting. Some of the boys do not know why they fight; they just do it for power and attention. We’re not going to stop until we rule the Vuras and if anyone stands in our way we will sort them out. I don’t care if they are the police, government or parents.”

When asked if rape was part of gang life, he answered, ‘We all rape girls if needs to be. If our enemies have sisters or siblings, we target them; we use them as weapons against our enemy. I have raped three girls already and one of my family members was raped by the enemy. You see, this is just a game and it’s going to go on and on in circles.”

Brazen attacks have taken place in schools. I was told that gang members will wear a neat school uniform, pretending they belong to that school. They then enter the school, find the enemy and stab him in front of his peers and teachers. In a documented incident, a group attacked a learner while he was standing in a line waiting to go to class. He spent a month in hospital recovering from a knife wound near his heart.

A police member from Harare police station admitted to me that he lives in fear of gangsters. “We are also human, as much as we are trained to be in control and in charge of certain events, but it’s difficult and scary when you have to arrest a gang member because the chances are the gang will target you afterwards.”

To younger children, the gangsters have become heroes. A five-year-old boy, accompanied by his friends from Town 2, explained to me how he had seen a gang member he knew being beaten by his enemies. He described how people had watched as the still-living gang member’s genitals were cut off. I asked him what he thought of the gangs in his area. He replied, “Ndiyabathanda mna, xabesilwa ndiyababukela, jiithi andiboyiki. Nathi xa sidlala nechomi zam silwa ngelahlobo kodwa sisebenzise amakhuni.” [I like them. When they fight I watch and I am not scared. Sometimes when my friends and I play, we would fight like that, but using sticks instead.] Many young boys I have met feel the same. They regard the violence they’re exposed to as quite normal. For them, a gang is an obvious place to end up.

In gang fights, panga wounds are common.

There is no respite from gang activities, even in death. A recent funeral of a gang member was attended mostly by youths, some in school uniform. There were few adults in attendance. Instead of hymns, the mourners sang their battle songs, which hearken back to anti-apartheid struggle songs. Shots were fired. Some youths were smoking weed and tik, others were drinking. A number of adults left because they felt the dead person was not being respected. A gang member told them that the family should step aside - it was the funeral of the youths’ friend.

A journalist taking pictures from the roof of a nearby shack was injured and his camera stolen by gang members. Weapons and a bottle of whisky were thrown into the grave. The funeral was followed by a party, after which the gang launched a hunt for the killer of the just-buried youth.

I asked some gang members how they became involved in gang life. Some said it was peer pressure when they were young. “If you hang around a certain crew, you’re bound to copy their habits,” one gang member said. “I was never forced to be in a gang. I saw my friends do it and I wanted to be cool just like them.”

Another gang member said, “In primary school we had dreams and got excited by the idea of high school. But now it’s not only about school but whether you survive the pressure of being seen as cool. Being in a gang in school is a way of gaining respect. Teachers can’t just talk to you as they please. Yes, we are there for books, for a better future. But what future do you have if you get killed? If you can’t beat them, join them.”

Some gang members have joined to seek revenge or because of the influence of family members. “I’m part of the gang because, two years ago, my brother was robbed and killed in Makhaza area,” one gang member told me. “I know who killed him and I want to make sure I kill those guys. Once you’ve started with a gang, it’s hard to go back to a normal life. The guy who stabbed my brother is in the wheelchair now.”

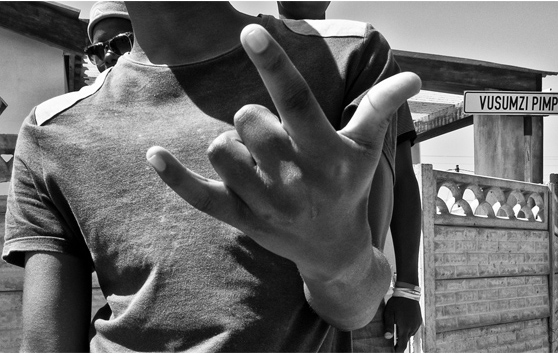

Terrors of the street, yet still in their early teens.

Not all the gangsters drink alcohol but most of them smoke tik. The drug wields huge influence in their lives. They claim it gives them the edge they need to do anything while maintaining a sense of calm. Much of the crime they commit is to sustain their tik habit. A gang member told me that not being high gave him a headache because he “thought too much” about things he was “not supposed to think about”, such as people he’d wronged or wounded. These thoughts, he said, were not good because they made him “go crazy”. To avoid them, he stays high. “Tik takes away problems and makes you forget about things,” he claimed.

Of course, there are deeper, less obvious reasons for joining gangs. These include:

It is extremely disturbing that parents, teachers, police and the entire community live in fear of teenagers who do what they please and kill with terrifying regularity. The search for solutions should deal not merely with prevention of gang violence but also its causes. Gang members are the children of recent migrants to the city who came in hope of a better life. What the city has given these youths is hopelessness, desperation and the knowledge that they will never enter mainstream society.

The general causes are poverty, a crumbling education system and social controls that lie in tatters. But we also need to ask questions about parenting, the presence (or absence) of fathers as role models and the prevalence of drugs. Perhaps the most important question for the young people who prowl the streets of Khayelitsha with knives and pangas is this: how does a boy become a man? If the only way offered is through violence, he will take that route. We urgently need to find other ways for teenagers to gain peer and social respect. When a five-year-old told me how much he enjoyed watching gang members beating people, I decided a start would be to document the problem as best I could. One person cannot fix the situation on her own, but this study is hopefully a step further along that path.

This article is published by the Safety and Violence Initiative of the University of Cape Town. A PDF version of this document with additional material and testimonies by children in gangs can be downloaded here.