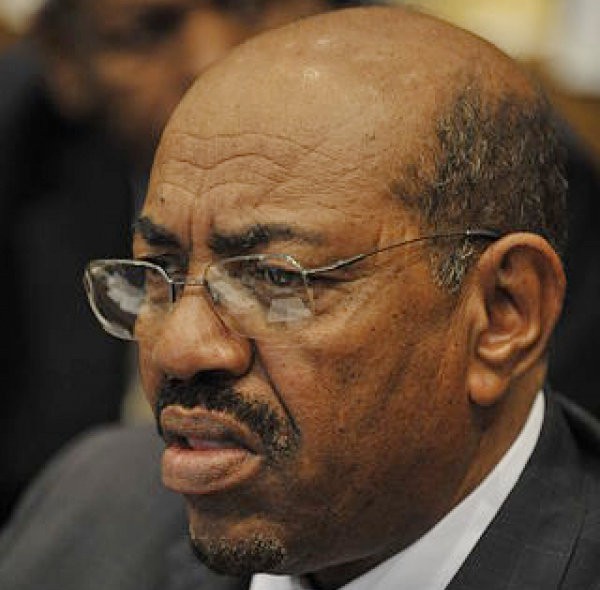

Government began taking steps to withdraw from the International Criminal Court after it failed to arrest the Sudanese President Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir (pictured) who is wanted by the ICC. Photo in public domain via Wikipedia

23 February 2017

On Wednesday, the Pretoria High Court ordered the Minister of International Relations, the Minister of Justice and Correctional Services and the president to revoke South Africa’s notice of withdrawal from the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC). While many celebrated the decision, the reality is that government can still withdraw from the ICC and the legal machinery to do so is already in the pipeline.

The court’s decision dealt with a number of issues but of greatest relevance was its findings on (1) whether the Minister of International Relations and Cooperation needed to have parliamentary approval before delivering the notice of withdrawal on 16 October 2016 and (2) whether a law called the Implementation of Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Act needed to be repealed before the Minister’s withdrawal.

To decide on these two issues, the court considered the Constitution. Under section 231(2), the executive (i.e. the president and Cabinet) can enter into international agreements, but these agreements only become binding when approved by Parliament. In the case of the Rome Statute, this approval came in the form of the Implementation of Rome Statute Act, which gave the Rome Statute status as national law. The process for entering into international agreements allows the executive to enter the agreements and seek parliamentary approval at a later stage. The issue was whether the same applied to withdrawal from an international agreement.

The court found that withdrawal from an international agreement has direct legal consequences and the executive therefore must have Parliament’s approval before withdrawing from an international agreement. Since the Minister did not have parliamentary approval before sending the notice of withdrawal to the United Nations, the withdrawal was invalid and unconstitutional. Also, the court found that the Implementation of Rome Statute Act should have been repealed before the notice of withdrawal was delivered.

However, while the withdrawal was declared invalid, the Implementation of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Repeal Bill (Repeal Bill) was recently tabled. The court found that the process for tabling this bill is “legitimately and properly before Parliament”.

Since the court found that the tabling of the Repeal Bill was “untainted” by the invalid withdrawal, the process of passing the bill will continue unimpeded. The bill was published for comment on 14 February. The public has until 8 March 2017 to comment. Following the comment period, the National Assembly, and then the National Council of Provinces, will vote on it. If the Bill passes, it will be sent to President Jacob Zuma for signature. Once this process is complete, the Government will be able to deliver a valid notice of withdrawal to the UN.

While the Repeal Bill may be challenged after it has passed, the courts have limited ability to intervene. It is government’s choice to enter into and withdraw from international agreements. While there may be room for small challenges to the Repeal Bill, the separation of powers means that a court is unlikely to make a ruling against the government’s decision to withdraw. This is because the courts defer to the democratically elected branches of government.

If South Africans do not want the government to withdraw from the ICC, they will need to actively participate in the democratic process. The comment and public consultation process is civil society’s opportunity to mobilise and stop the government from taking decisions that may be unjust albeit lawful.

During the height of Aids denialism, the Constitutional Court ordered the government to make antiretrovirals available to HIV-positive pregnant women to prevent their babies from becoming infected. However, it was because thousands of people picketed, marched and debated publicly that government finally made antiretrovirals available, in principle, to everyone with Aids, and that today there are nearly four million people on antiretroviral treatment in the country. That was not a feat achieved through the courts, though the courts helped. Even more recently, President Zuma referred the Expropriation Bill – and five other Bills – back to Parliament because of objections his office received.

Comments on the withdrawal bill can be emailed to Mr. V. Ramaano at vramaano@parliament.gov.za.

Public hearings will be held at Parliament. To attend and participate contact Mr V. Ramaano on (021) 403 3820 or 083 709 8427.

Progress of the Bill can be tracked here.