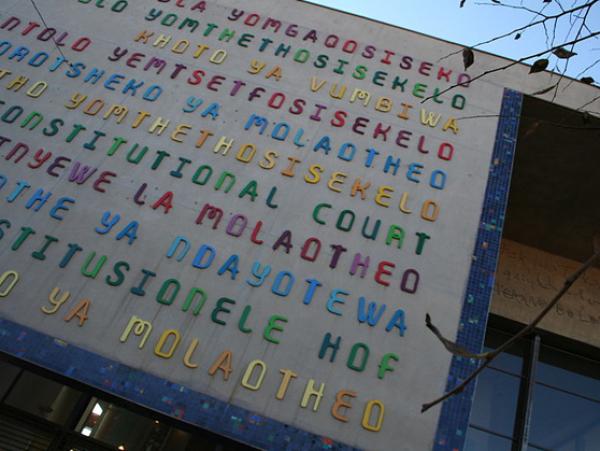

Entrance to the Constitutional Court. Photo by Wikipedia user André-Pierre (CC-BY-2.0).

9 July 2015

The Judicial Service Commission is interviewing four candidates for the Constitutional Court today and tomorrow (9 and 10 July). Alison Tilley of the Open Democracy Advice Centre explains why this week’s process matters so much.

Why is picking a new Constitutional Court Judge a big deal? Mostly because theirs is the last word on what the constitution means.

There are people you know that are alive because of the court’s decisions. From whether the right to life means the death penalty can continue (their answer: no) to whether state health services can refuse an affordable effective medical treatment on unreasonable grounds (their answer: no), their yes or no is the last word on those issues. They pretty much can’t be fired, and serve for one term only. And they cannot be overturned on appeal.

So selecting a new judge for the Constitutional Court is important. Really important. So you would think that the discussion about what makes for a good judge on the constitutional court would be a matter of some debate. It has been.

But that has been overtaken by some politicians complaining about judges, and whether they are ‘observing judicial deference.’ That basically means: stop ordering us politicians to do stuff we don’t want to do, because no one elected you.

That line of criticism is an old one, and always worth a bit of airing if you are a politician who has lost one too many court cases. But in this instance the state isn’t just losing a few cases, or even many cases – it has just been found to have ignored a court order in a very, very high profile court case.

In the current incarnation of the debate, it involves hard core politicians coming out and saying that the courts have overstepped their mark, and strayed into the realm that they — elected representatives of the people — legitimately claim. Mostly, for this issue, that is usually about it. Judges judge. Politicians grandstand.

But in this instance on 8 July 2015 a statement was issued by the Chief Justice, the Heads Of Court and the Senior Judges of all Divisions. It was found necessary to title the statement: The Judiciary’s Commitment To The Rule Of Law. In this statement, which was issued in an unprecedented show of solidarity by judicial officers, the Chief Justice says, on behalf of the bench:

The Rule of Law is the cornerstone of our constitutional democracy. In simple terms it means everybody whatever her or his status is subject to and bound by the constitution and the law. As a nation, we ignore it at our peril.

Does this mean that there is a drawing of battle lines in the sand? And if it does, what does that mean for the process of picking of judges for the constitutional court? I think it means trouble.

It means that the Judicial Services Commission hearing, which generally divides in seating arrangements into lawyers on one side, and politicians on the other, risks degenerating into a debate between the two sides, conducted by asking the judges being interviewed questions like “So, what do you think of the separation of powers?” Which is like asking a traffic policewoman if she is in favour of traffic lights. The answer is almost always yes. Because they are legal, and useful.

The key thing that will be lost in such a focus on such an bland question, is what the candidates think about the many legal issues they are grappling with, only 20 years into trying to figure out, line by line, comma by comma, what the whole text of the Constitution means. And what they think is of even more importance now, in this round of hearings, because the “174 criteria” are going to be of little help in putting one candidate forward or another. These are the criteria which ask the JSC to appoint judges, provided they are fit and proper, with a view to transformation. The current candidates are all women. None of them are white.

The only way for the differences between then to emerge is for the JSC is to ask them solid questions that have some depth. There are differences for sure. Of the candidates, Judge Pillay is the most junior of the judges, from KZN. Will that lack of seniority count against her? She has some interesting judgements, though. On the subject of rape in one judgement she says “… [T]he proceedings were conducted by an all-male team of magistrate, prosecutor and defence attorney. It is not clear from the record whether the interpreter was also a male. If he was, this would have aggravated the child witnesses’ ability in communicating effectively. … Rape victims, adults and children alike have great difficulty in expressing their experiences dispassionately and coherently.” That’s the sort of thing most judges don’t comment on, let alone express so well.

Judge Theron is the judge who has spent the most time acting in the constitutional court. She considered an appeal in a case where the appellant had been convicted of rape and kidnapping. The complainant had been locked in a room with the rapist for the entire night. As the appellant was convicted of raping the complainant five times, the High Court sentenced him to life imprisonment. The appeal court then reduced the rapist’s sentence to 16 years.

Judge Theron said in a dissenting judgement that “in my view, the rape of the complainant is one of the worst imaginable. If life imprisonment is not appropriate in a rape as brutal as this, then when would it be appropriate?” She would have upheld the sentence.

But giving long sentences is not the measure of a good judge. Trying to make sure trials are fair is an important part of ensuring justice is done. Look at a decision of Judge Mhlantla, the third candidate. In that case the complainant, who was 54 years old at the time, was raped by four men; one of whom was a family member. The accused decided to plead guilty to the charge of rape. There are different kinds of rape charge, with different sentences. These are minimum sentences, introduced in order to make sure a serious enough sentence is given in rape cases. They were told at trial that they were being charged with a section of the law that gives a ten year penalty for rape. They were then sentenced to life, under another section. Still rape, but the section on which they pleaded guilty and, importantly, on which they were convicted, had a ten year sentence.

Judge Mhlantla considered mitigating factors submitted on behalf of the appellants including that the complainant did not suffer severe physical injuries albeit the incident would have traumatised her. She sentenced them to ten years, “Having regard to all circumstances, I am compelled to impose a sentence of ten years’ imprisonment as set out in s 51(2) of the Act.”

Does that make her a better judge for the accused than Judge Pillay? Or a worse judge for the victim than Judge Theron? It’s just impossible to say things like that given the nature of each case. They are all different, and in each case, each judge could reach a different decision, if there are different facts. But is there a judicial philosophy that the judge could talk about in the hearings, and explain?

If there is, and there probably is, we need to know that. We need questions asked that will delve into these hard issues. A simple drawing of battle lines, and the issue of judicial deference being batted between politicians and lawyers will not accord these judges, with years of experience and a track record of excellence, an opportunity to explain what judges think. We need to know that. Judges are important, and that must not be lost in this week’s version of the separation of powers debate. Politicians will have moved on soon – this judge will be here for some time to come.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.