Photo licensed under CC by-nc-sa 2.0 courtesy of John Dewar.

12 December 2012

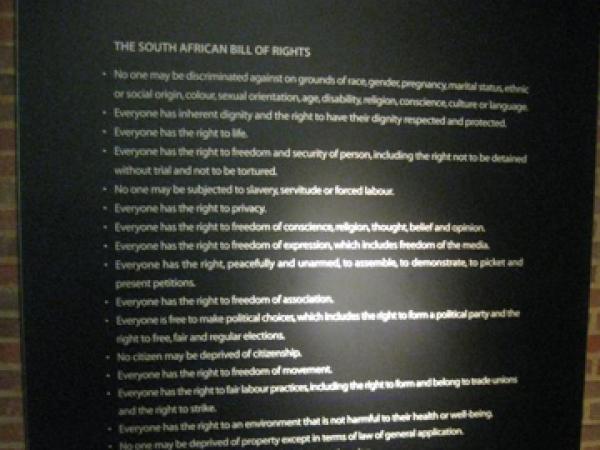

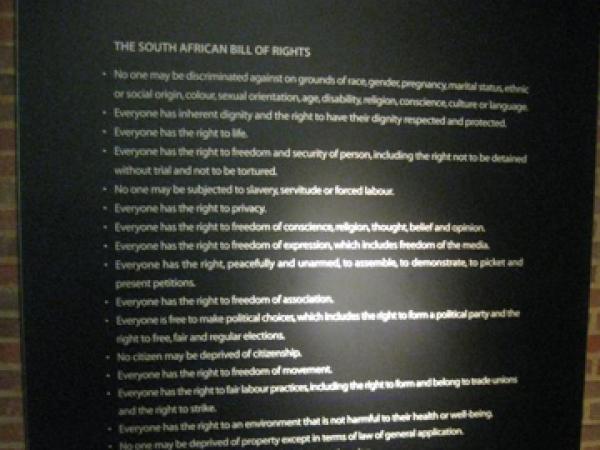

The Bill of Rights is rightly hailed throughout the labour movement and beyond as perhaps the finest exposition of the desire of the bulk of humanity for a world that guarantees the maximum level of dignity, equality and freedom for all.

It is also the greatest legacy of the late chief justice Arthur Chaskalson. At the time it was adopted in 1996, he paraphrased the first sentence, noting: “The Bill of Rights is the cornerstone of our democracy.”

Words along similar lines have been uttered throughout this week by the likes of trade union leaders and politicians — all the great and the good and not-so-good — who paid tribute to a man who laid that cornerstone on which so little of substance has been built. However, lip service is continually paid to the principles of dignity, equality and freedom for all that should form the practical foundation for a truly democratic society.

The blueprint — the programme — for such a society exists in the schedule of Rights contained in Chapter 2 of Act 108 of 1996. It would certainly have the support of most people everywhere since it proposes a world that would change utterly the situation of islands of obscene wealth surrounded by an increasingly volatile and growing mass of poverty and degradation.

The responsibility for this, say the unions and their allies, lies with a system that promotes gross inequality. So they demand a change of political direction; for economic policies and greater regulation to ensure more fairness and equality within the system.

However, as some critics are prone to quote, this might be seen as hoping that “the nastiest of men for the nastiest of motives will somehow work for the benefit of all”. But the blame for the mess we are in has also been laid at the feet of the majority of people.

According to political leaders ranging from reserve bank governor Gill Marcus to planning minister Trevor Manuel and basic education minister Angie Motshekga a largely apathetic populace is responsible for the fact that the cornerstone of democracy is not being built on. Speaking about the Limpopo textbooks debacle at a National Union of Metalworkers (Numsa) conference last week, Marcus noted: “If textbook weren’t delivered, why didn’t someone fetch them? You talk of action: that’s action.”

Similar sentiments were expressed by Manuel at a conference in Cape Town in September. He stressed that the Constitution could not be blamed for the slow pace of change in South Africa. “The Constitution empowers and enables, but beyond that, actual change requires human actions,” he said.

It almost seems a case of politicians wishing to dissolve the people and elect another. Because the same politicians, sometimes in the same speeches, castigate actions by unions and others that are clearly aimed at bringing about change that is in line with the Bill of Rights.

In an often messy and muddled way, this is precisely what has been witnessed in many of the countless “unrest incidents” around the country and, most dramatically, in the platinum-rich lands of the Bafokeng and the fruit and wine farms of the Boland. However, few of the participants in these strikes may be aware of — or have read — the Bill of Rights; they are merely trying to claw their way to greater equality and freedom.

Most tend to see this in terms of better wages, an understandable reaction in a society where material wealth determines degrees of equality, freedom and even access to formal justice. But in the process, there have been glimpses of the egalitarian order envisaged by Chapter 2 of Act 108. These are examples of direct democracy in action, of democratic committees, electing a first among equals to speak for the group.

These are practical manifestations of the hollow, “Let the people speak” rhetoric of most politicians. As a result a few voices, mainly within the labour movement, are continuing to ask: Why not establish a system that, within the bounds of the Bill of Rights, truly lets the people not only speak, but also decide?

After all, the argument goes, technological advances, leading to greater automation and mechanisation, are making more and more of humanity redundant, in the process causing hideous social and environmental harm. This was highlighted again last week with reports about Japanese scientist Hiroshi Ishiguro who has made a robot double of himself that can deliver lectures.

Mining companies and farming interests have also, in recent weeks, made it clear that increased wages will mean greater mechanisation and fewer jobs, accelerating a process that is probably unstoppable.

But, as some labour activists argued in this column in June, the very same technological advances have turned the world into a village in terms of communication. That makes South Africa a small region of that village and, despite gross disparities of income and minimal home internet connections, more than 12 million South African adults now regularly use the internet.

This figure comes from a major survey published last week. It reveals that these internet users access this means of almost instant communication by means of cell phones, computers based at schools, universities or other institutions and at internet cafes. In other words, the means now exist for citizens en masse to hear about, discuss, analyse, and make decisions about their lives.

The missing ingredient is organisation. Because, on the basis of available technology, union locals, religious communities, schools and communities could be transformed into democratic hubs where citizens debate, discuss and vote on all matters concerning them — and instruct recallable members of government to implement majority decisions.

This is an idea that will not feature at Magaung, but one that may become much more prominent within the labour movement, especially in the wake of the recent wildcat strikes. These have been a wake-up call to unions: in order to remain relevant, they should look to their democratic roots and assess how best to return to them. The technical resources exist. Only imagination and political will are missing.