6 July 2015

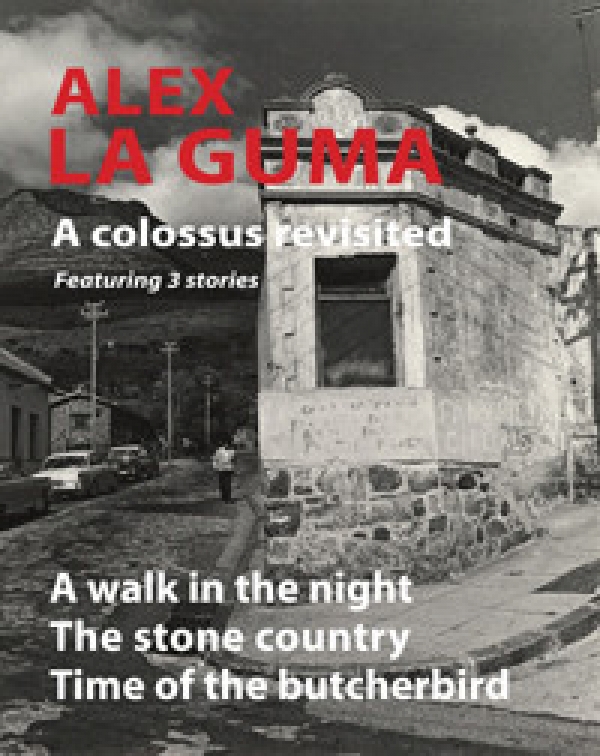

“Alex La Guma has come home.” With those words, a visibly emotional Blanche La Guma last weekend received the first book, “hot off the presses” containing three of her late husband’s best-known novels, all of them banned in the apartheid era. The occasion was the initial launch of Alex La Guma - a colossus revisited at the literary festival in the small Western Cape resort town of Montagu.

The works of La Guma — regarded internationally as one of South Africa’s finest writers — are still generally unavailable in South Africa and his name is little known, especially to younger generations. Yet his five novels and his numerous short stories are standard texts in many university African literature courses around the world.

Often described as a South African Dickens, La Guma was also a poet and painter who sketched, wrote radio plays and drew the polemical Little Libby comic strip in the anti-apartheid New Age newspaper in the early 1960s. Justly renowned for his eye for detail and vivid style, he was also a political activist and communist who was banned, house arrested, jailed and tried for treason.

The 1956 treason trial, which dragged on for four years, saw 156 anti-apartheid activists charged following the 1955 Congress of the People in Kliptown that gave birth to the Freedom Charter. La Guma was one of the congress organisers, but was arrested at Beaufort West on his way to the gathering.

During the trial, La Guma wrote a series of articles for the publication, Fighting Talk in which he vividly described not only the proceedings, but the atmosphere at the trial. This ability to create graphic word pictures of scenes, emotions and motivations was his forte and led to him being compared to Dickens.

So far as the regime and its security police were concerned, his writing was dangerously subversive and needed to be destroyed. So the police frequently raided the La Guma home, abusing adults and children alike as they confiscated any manuscripts they could lay their hands on.

It was a frightening and bitter time, but La Guma kept on writing, his own experiences providing additional grist to a mill of humanism spiced with anger that reflected the lives of millions of fellow oppressed. And he never lost his sense of humour, noting once that he should have thanked the apartheid state for sentencing him to 24-hour house arrest in 1961. “Gave me time to finish A Walk in the Dark,” he remarked.

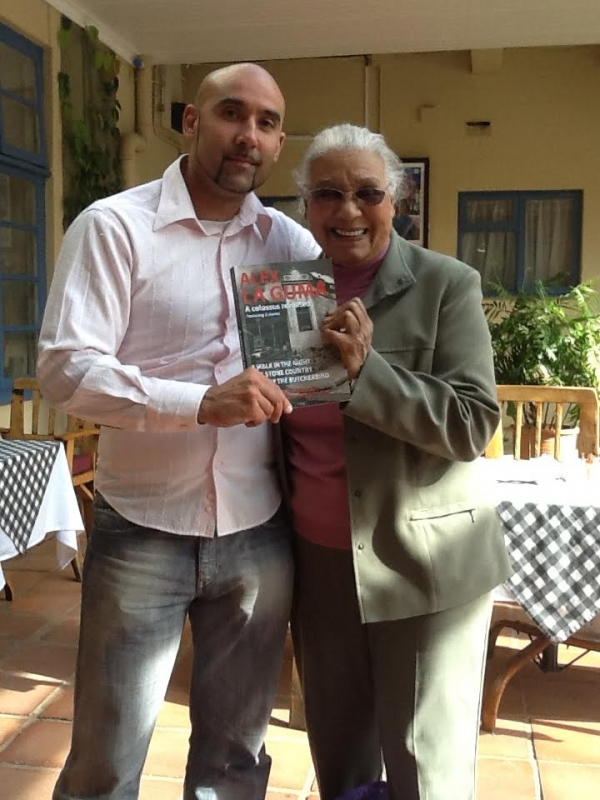

Lindsay Johns and Blanche La Guma hold up a copy of the book. Photo courtesy of Lindsay Johns.

That novella, the first in the new book, is also based very much on personal experience and keen observation, being set in District Six, Cape Town’s inner city area in which he grew up. Down-at-heel, sleazy, sordid and, at one and the same time exuding both desperation and desperate hope, District Six epitomised the devastation visited on communities by apartheid and capitalism.

However, there is nothing dated, parochial or preachingly polemical about any of his works; their themes are universal and timeless. Alex La Guma knew first hand the humanity that underlay the often brutal lives whether in the sordid squalor of the District Six tenements of 1960s Cape Town, the prisons of apartheid or the rural areas.

These are the settings of the three tales in this new book that spans 17 years of his writing. Along with A Walk in the Night (1962), there is The Stone country (1967) and Time of the Butcherbird (1979).

Alex and Blanche La Guma and their two children went into exile in 1966 and Alex died in Cuba in 1985 where he was the effective South African ambassador, representing the ANC. This latest collection contains a foreword by former constitutional court judge Albie Sachs, and an introduction by British writer and broadcaster Lindsay Johns.

Blanche La Guma, now 87, has also contributed a brief autobiographical account of her life and with Alex. The book will be formally launched in Cape Town on July 15 at the Book Lounge.