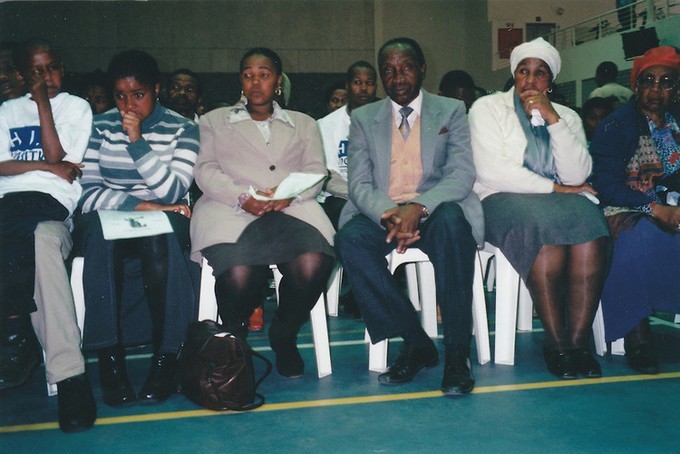

Funeral of AIDS treatment activist Christopher Moraka on 8 May 2000. Source: Treatment Action Campaign.

1 February 2016

Four articles so far. More than 7,000 words. Yet in Thabo Mbeki’s attempt to salvage his legacy, not once has our former president mentioned HIV. (Read articles one, two, three and four.)

In today’s missive, which is even less penetrable than usual, Mbeki appears to defend himself from the charge of being aloof. He is upset that this accusation contributed to his defeat by Jacob Zuma at Polokowane in 2007.

But leaders are not looked upon unkindly by history solely for a subjective personality trait such as aloofness. Mbeki’s reputation doesn’t rise or fall on whether he was aloof, too intellectual or even authoritarian in his personal relationships. It is deservedly and unalterably shattered for a much clearer reason: he pursued policies that resulted in hundreds of thousands of people dying, most of whom might otherwise have still been alive today.

On 10 December 1998, a handful of people held a protest on the steps of St George’s Cathedral. They had two main demands for government: (1) Make a plan to introduce an antiretroviral called AZT for pregnant women with HIV. (2) Develop “a comprehensive and affordable treatment plan for all people living with HIV/AIDS.”

That was the modest launch of the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC). It took nearly four more years, two court orders and many large demonstrations before the state reluctantly began rolling out a countrywide mother-to-child transmission programme in 2002. It would take until March 2004 before antiretroviral treatment became available as a matter of policy in the public health system. And then only after more protests, the intervention of Nelson Mandela, a civil disobedience campaign and legal threats. By contrast, Botswana began its treatment programme in January 2002.

Even after the antiretroviral treatment rollout began, Mbeki’s Minister of Health undermined it. She and the Medical Research Council under Anthony Mbewu gave and received support, both material and moral, to and from the charlatan Matthias Rath.

Rath ran double page newspaper advertisements across the country dissuading people from taking antiretrovirals. Instead, he encouraged them to take his vitamin products. He ran an unauthorised clinical trial, an extremely serious crime for which he can be tried if he ever returns to South Africa, under the nose of the Minister. His colleagues presented “results” of this trial at a meeting with the minister and the provincial MECs for Health (p. 56). She defended him publicly.

Meanwhile people died on Rath’s clinical trial. They too might be alive today had they sought treatment in the public health system. It took two court cases by the TAC to run this murderous quack out of the country.

There was much else: co-option by the Department of Health of NAPWA, a major organisation representing people with HIV, support of several other charlatans – at least one of whom was even given an opportunity to present to a parliamentary committee (p. 87) to the applauds of the ANC members present. And let’s not forget Virodene and Mbeki’s purge of the Medicines Control Council because its chair dared to call him out (ch. 8). Nearly two decades later that once internationally renowned institution has still not recovered.

Mbeki disputed there were many AIDS deaths. He was supported by Rian Malan, South Africa’s finest proponent of bonzo journalism (the use of wit and word play to disguise a lack of integrity and knowledge). This likely earned Malan a favourable mention in Mbeki’s 2004 State of the Nation Address.

Two studies, conducted independently of each other, have estimated that the delayed treatment rollout caused well over 300,000 avoidable deaths. These estimates are conservative. Without the robust response by civil society to Mbeki that ultimately resulted in the change in government policy, many more would have died.

You could argue that Mbeki made a mistake, that he got it unintentionally wrong, that there was no malice in his AIDS denialism. But Mbeki chose to ignore the country’s scientists and doctors. These included Malegapuru Makgoba, who headed the Medical Research Council (before being replaced by Mbewu), Kgosi Letlape who headed the South African Medical Association, respected researchers Quarraisha and Salim Abdool Karim, and many others.

Mbeki also ignored ordinary people with HIV like Christopher Moraka. In 2000 Moraka, dying of AIDS-related illnesses, appeared before Parliament and pleaded for pharmaceutical companies to drop the prices of AIDS medicines. He died long before the companies or anyone in cabinet listened. Mbeki, his Miniser of Health, Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, and his Minister of Trade and Industry, Alec Erwin, barely lifted a finger to help bring down drug prices. That was left to TAC and other civil society organisations.

Instead Mbeki hosted his absurd AIDS advisory panel, half of whose members were AIDS denialists. He was photographed – smiling, not aloof – with an outspoken, now dead of AIDS, denialist. He questioned whether a virus can cause a syndrome, and continuously cast aspersions on proven antiretroviral treatments.

Whether or not Mbeki was aloof is irrelevant. What matters is that he caused enormous suffering and death. He should consider himself fortunate to have escaped prosecution. Instead of indulging in impenetrable revisionism, he should maybe consider penance by living the rest of his life quietly, pursuing good deeds. Perhaps he, as well as his chief apologist Frank Chikane, could start by washing the feet of the surviving members of Christopher Moraka’s family.

Geffen is GroundUp’s editor. Views expressed are not necessarily shared by GroundUp’s staff.