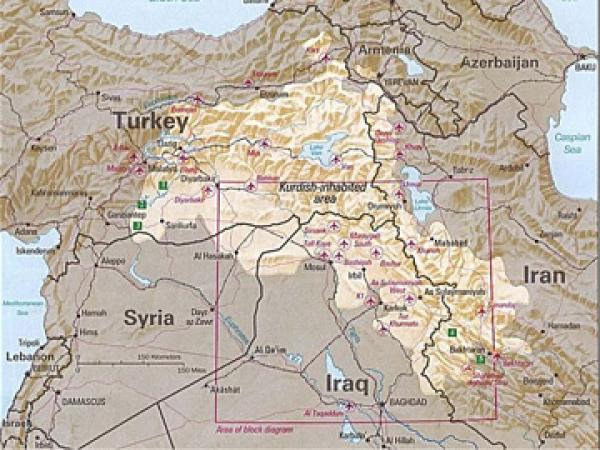

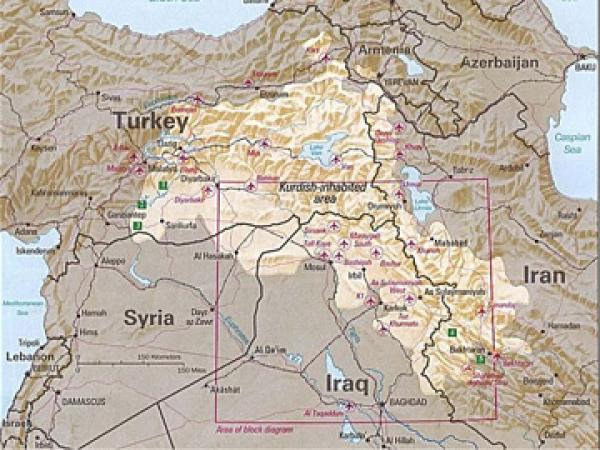

Kurdish-inhabited area, by CIA (1992). Wikimedia commons.

5 August 2013

A process has begun in Turkey which has the potential to find solutions to the Kurdish question.

Turkey has held initial talks with Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan at his Imrali Island prison. Various groups and prominent individuals on both sides have come out in support of a peaceful, negotiated settlement to the long-standing Kurdish issue.

In a significant move, the Kurdistan People’s Party (PKK) declared a ceasefire in the 29-year armed conflict with the Turkish State in April this year and withdrew its guerrillas to the movement’s base in the Qandil Mountains in Northern Iraq.

The conflict has claimed the lives of some 40,000 people, most on the Kurdish side. Ocalan, a widely respected resistance leader, was abducted by Western intelligence groups in Kenya in 1999 and handed over to Turkey. He was first sentenced to death for treason and then had his sentence commuted to life imprisonment. He has served more than 13 years on the Island prison, much of it in total isolation.

In order to have a better understanding of the Kurdish question, it is important to understand a bit about the history of the people and the politics in that region.

The chairperson of the Kurdish Human Rights Action Group (KHRAG) in South Africa, Judge Essa Moosa, says the Kurds initially lived in their own country which was commonly known as Kurdistan. It was situated between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.

“It was regarded as the cradle of civilization. Prophet Abraham who is regarded as the father of the Jews, Christians and Muslims is reputed to have come from a place called Urfa situated in Kurdistan.”

“The Kurdish people have all the attributes of a nation. They have their own 5,000-year-old language, their culture, customs and practices, holidays and festivities, songs, dances and national dress handed down from generation to generation over centuries.”

Newroz, the Kurdish New Year, is an important festival that is celebrated with great fervour, coinciding with the spring solstice which falls generally on 21 March.

The Kurds were a nomadic people who lived in mountainous terrain. While their principal religion is Sunni Islam, there are significant Shiite, Christian and Jewish minorities. Yazidism or the “cult of the angels” is also a minor faith.

The Kurdish language belongs to the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European Language. The language, which has at least four major dialects, has been vigorously suppressed in almost all the countries the Kurds live in. Restrictions relating to its use on radio and TV broadcasting exist in almost all these countries. In Iraq, under the new constitution, the language has been granted official status.

There is no universal script for the Kurdish language. The script in use depends on the geographic location. In Iran and Iraq, for instance, the language is written using a modified Arabic script, while, in Turkey and Syria, the Latin script is used.

Kurdistan used to be part of the Ottoman Empire. With the collapse of the Empire in the early part of the last century, the colonial powers of Britain and France divided up the region. A number of agreements were reached between 1915 and 1917 in terms of which the Ottoman Empire would be partitioned and Kurdish areas would fall under the control of Britain, Russia and France.

A Turkish resistance movement emerged in Anatolia and their campaign resulted in the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, which led to the establishment of the Republic of Turkey.

This left the Kurds stateless and facing a future as oppressed minorities in four countries – Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria.

Since then the Kurdish people, like the Palestinians, have been fighting for their freedom, independence and basic human rights.

In all four countries they find themselves in, there have been attempts to deny them their identity as Kurds, the right to speak their language, practise their customs, sing their songs, educate themselves in their mother-tongue, belong to their own organisations, or to have their own newspapers, radio stations and TV.

Various separatist Kurdish movements emerged over the years and were violently crushed. The Kurds have suffered terrible violence over time, the most brutal being the poison gas attack on thousands of Kurds by the Saddam Hussein regime and the razing of hundreds of Kurdish villages during military rule in Turkey.

Kurds have been denied basic cultural and political rights and have had to endure immense repression over decades. Turkey’s constitution makes no provision for the recognition of Kurdish identity. There has been a long process of assimilating the Kurds, which included among other things the suppression of their language.

With the support of the United States and other Western Powers, the regime in Turkey has continued to visit the most extreme repression on the Kurdish minority population of 20 million people, both during and after military rule.

Presently in Turkey, despite talks about peace, there are more than 8 000 Kurdish activists, politicians, mayors, professors, academics, writers, children and women either in prison or on trial for political offences.

A Kurdish TV station, Roj TV, broadcasting from Copenhagen to millions of Kurds worldwide, was recently closed down by order of a Danish Court. It is widely alleged that this was a political decision, taken at the behest of Turkey.

Turkey is regarded as one of the worst violators of media freedom, and the Kurdish media have been prime victims. A number of lawyers, including the representatives of Abdullah Ocalan have appeared on various charges over an extended period of time.

It does appear that, like South Africa in the early 1990s, a joint strategy of repression and reform is being pursued. Nonetheless, the question of a peaceful negotiated solution to the Kurdish question still remains on the agenda.

Currently there are approximately 40 million Kurds in the World. There are 20 million Kurds in Turkey; 8 million in Iraq; 7 million in Iran; 3 million in Syria, and two million spread over the world, with the majority in Europe.

Initially, Kurdish demands included the re-establishment of Kurdistan but in recent years they have spoken more of regional autonomy within a constitutional democracy.

The Kurds demand to be recognised as a national group in a democratic country in which they can enjoy basic human rights, freedom, dignity and equality–a country in which they will be free to form their own political, civic and social organisations, and in those areas where they form the majority, to enjoy political autonomy or self-rule.

KHRAG believes that a number of important steps have to be taken for peace negotiations to have any meaning. It said recently in a statement: “Firstly, the repression must stop. Secondly, the climate for bona fide negotiations must be created through releasing Abdullah Ocalan and other political prisoners, unbanning Kurdish organisations, allowing exiles to return, scrapping repressive legislation such as the anti-terror law and permitting free political activity.”

KHRAG is of the view that there can be “no permanent political solution to the problem of the Middle East without the recognition of the Kurdish people as an important role-player.”

“To declare the leaders of the Kurdish people or their organisations as terrorist, only compounds the problem. They are part of the solution and not part of the problem”, declared KHRAG.

KHRAG has called on Kurds and Turks to “grasp this historic opportunity and take it to its logical conclusion”.