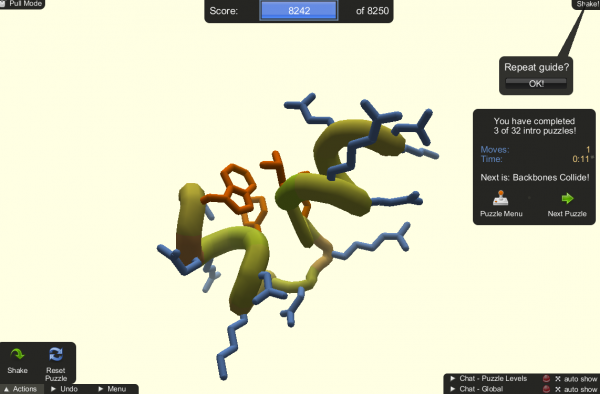

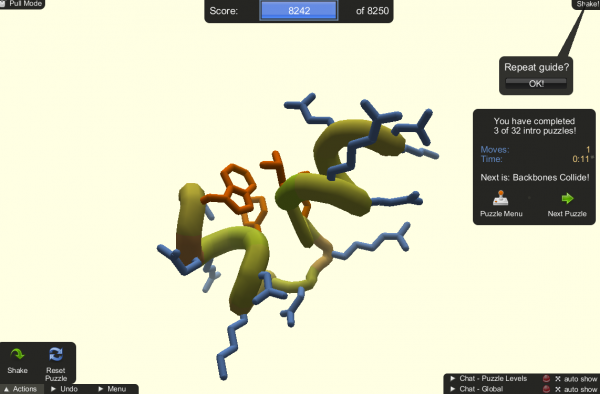

A screen printout from a FoldIt game.

3 April 2013

This is the first of an occasional new feature science column from GroundUp. We hope these short articles will make science more popular and encourage learners to study science. Today’s article by Kerry Gordon describes how in 2011, game players solved a difficult science problem.

In just three weeks, a group of computer gamers solved a tricky problem that AIDS researchers had been trying to figure out for years. Teams of players competed against each other to see who could solve the problem. Most of the players in the teams that won included players with no training in this field of research; all each of them had was a computer and an internet connection, which they used to become part of a vast human supercomputer.

They were playing a game called Foldit, which is used to work out the 3-D shape of proteins. Proteins are molecules that do the work in our bodies like digesting our food, controlling our moods and protecting us from diseases. Each protein has a specific job, and for it to work properly it needs to fold into an exact 3-D shape. If it doesn’t fold properly then it can cause diseases like Alzheimer’s, diabetes and cancer.

If we can work out the 3-D structure of a protein then we can understand it better, and in the case of diseases, this is an important step towards finding a cure. The problem is that we don’t know enough about how proteins fold to be able to predict the 3-D shape of an unknown protein – and that’s where Foldit comes in.

Foldit is the brainchild of the Center for Game Science and the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Washington, Seattle. It was created to improve the way we work out the 3-D structure of proteins. Most protein structures are solved by doing experiments that are slow, expensive, and likely to fail; so computer programmers have stepped in and are writing software to predict the way that proteins will fold. The problem is that these computer programs aren’t very good - yet. So Foldit takes the problem and turns it into a game, using hundreds of eager players to fold proteins, again and again, in different ways, spreading the load of trying out the thousands of possible combinations. It’s an experiment to see whether humans are better than computers at working out protein folding, but it also takes strategies that humans use to fold proteins, and uses them to make the computer programs work better. Amazingly, players don’t need to understand biology to play, though the game can teach players a lot about biology.

In 2011, Foldit players beat scientists at their own game and made the best prediction of the 3-D structure of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (M-PMV) retroviral protease, a protein in SIV, the monkey equivalent of HIV. The gamers came up with a predicted 3-D structure that helped scientists find sites on the proteins that can be used to design drugs to treat SIV and HIV. The teams that contributed most to this effort had fun names: Contenders Group and Void Crushers.

Foldit is part of a growing movement of citizen science, giving ordinary people an opportunity to be part of huge research projects, while scientists get the benefit of hundreds or even thousands of people helping them do their research. Citizen science is a key part of creating a scientifically aware community – people who are actively involved in science, who have the information and understanding to make informed decisions.

In the past, citizen scientists were bird-watchers, botany enthusiasts or amateur star-gazers who could volunteer their time to help scientists because they had a little bit of knowledge about what to look out for. With easier access to the internet, scientists can reach a much bigger group of potential volunteers. By designing enjoyable software and games, they are getting a lot of help solving some tricky problems and teaching ordinary people more about science.