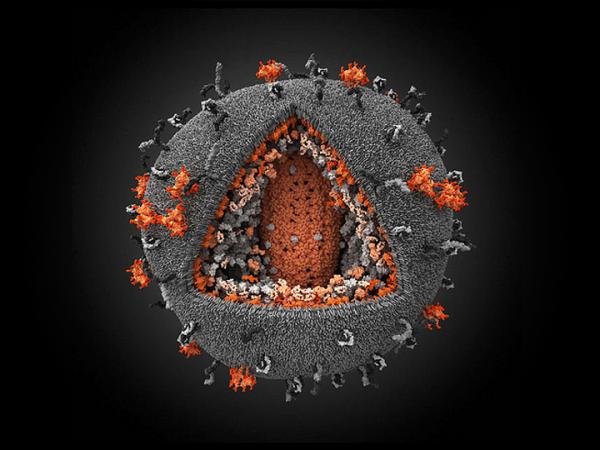

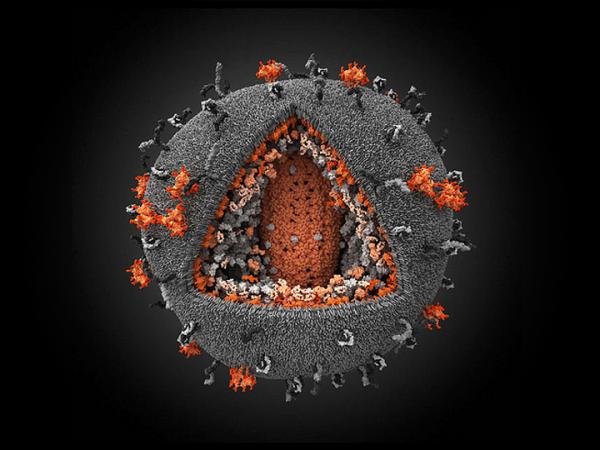

Image by Ivan Konstantinov, Yury Stefanov, Aleksander Kovalevsky, Yegor Voronin, Visual Science Company (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

9 October 2013

While antiretroviral drugs against HIV are getting more effective and allow HIV-positive people to live longer, the ultimate prize is to find a way to cure people of the virus, the best hope being a vaccine.

The HIV vaccines that have been tried so far have failed because the virus is so good at mutating, making it undetectable to our immune system. HIV also lies dormant in some cells, hiding from attack, ready to strike as soon as we are vulnerable. These have been tricky to find and the virus has managed to slip out of the immune system’s grasp.

In a new study, researchers think they may have a different approach. By using another virus, we can alert the cells that are blind to HIV.

Researchers added a mix of the primate version of HIV called Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV) and DNA from a virus called Cytomegalovirus (CMV) to Rhesus monkeys.

CMV is a virus related to the herpes virus that infects humans, it is fairly harmless for healthy people, but is dangerous for those with a poor immune system. CMV is more easily detected by our immune cells and can be wiped out. By using a mixture of CMV and SIV, the researchers think that they have managed to activate the immune cells in a way that enables it to destroy HIV.

They found that about half of the monkeys that got infected managed to fight off the SIV infection. When they infected the monkeys with a potent strain of SIV, they managed to get rid of the infection with no trace of the virus after three years.

This is unheard of in humans. There are only two cases where it seems we’ve managed to cure patients of HIV.

Timothy Brown, known as the ‘Berlin patient’, was HIV-positive and was diagnosed with cancer. He had to have a bone marrow transplant to treat the cancer. His doctors used cells from a donor that mutated, effectively endowing Timothy Brown’s immune system with HIV-proof cells. No trace of HIV has been detected in his blood. But a bone marrow transplant is extremely expensive and dangerous. It is not a practical way to cure people of HIV.

The Mississippi baby has been reported as the first “functional cure” of HIV in a child. The baby’s mother was living with HIV. She was treated with antiretrovirals from the birth of her child. HIV has not been detected in the baby’s blood after twelve months of treatment.

In both these cases it is not clear whether the patients are cured of HIV or not. There is no evidence that HIV is active in their bodies, but we cannot be sure of this because there is no known way to obtain samples of the cells where HIV could be hiding without harming the patient.

In the SIV experiments, the scientists could verify that the infection had been cleared by doing a necropsy (the animal version of an autopsy) and examining different tissues to try to find traces of the virus. Early testing of drugs is carried out on animals so that we can find out how the treatment works, and what the possible side-effects may be. But there are limits to using biological similarity between humans and animals: a cure for SIV in monkeys may not work for HIV in humans. Some philosophers argue that experimenting on monkeys and apes is unethical. Others counter that that these experiments are essential for finding new life-saving medicines.

The researchers who developed the CMV-based vaccine plan to test whether it can cure monkeys already infected with SIV (as opposed to trying to infect them after they’ve received the vaccine). This will help scientists understand more about how the vaccine works and what its potential is as a treatment for HIV-infected people. No matter what the outcome, we will have made some progress towards understanding the battle between our immune system and HIV.