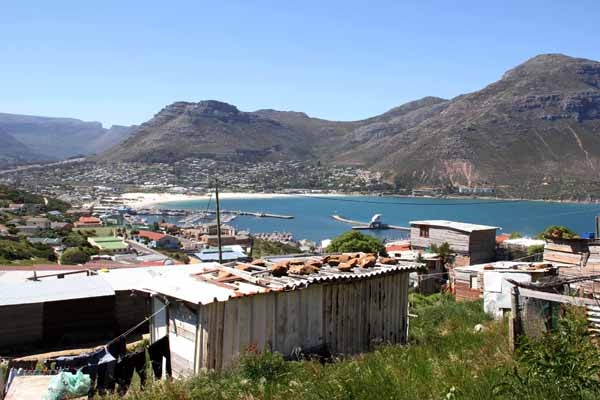

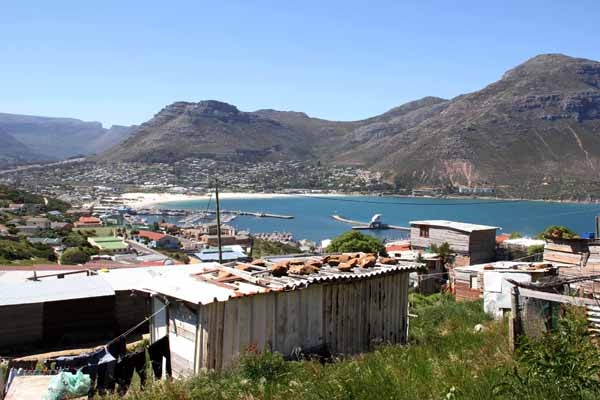

The view from Die Sloot informal settlement in Hangberg, Hout Bay. Photo by Daneel Knoetze.

8 October 2014

Four years after the riots of 2010, Hangberg is on the edge of rebellion. Protests after the arrest of resident Santonio Jonkers engulfed the neighbourhood last week and a traditional leader has warned of impending bloodshed. GroundUp finds out why the 2011 Peace Accord between the community and the authorities seems to be in tatters.

Naked and bound, Santonio Jonkers was dragged by his dreadlocks for 150 metres through fynbos and wattle trees, by an elite squad of police officers in the early hours of September 30. Semi-conscious from the beating which preceded his arrest, he was thrown into a Casspir and rushed from his home on the Sentinel to a holding cell in Stellenbosch. There, the beating apparently continued.

Santonio Jonkers was arrested and beaten by the police for being in contravention of a court order interdicting against further settlement at Die Sloot. Photo by Daneel Knoetze.

Several witnesses saw the arrest and CCTV from a nearby house shows that a total of 18 officers, some from the elite National Intervention Unit, went into Die Sloot to extract Jonkers.

The violence of the arrest spurred Hangberg’s residents into a rage reminiscent of the uprising in September 2010.

Die Sloot, an informal settlement of a few dozen shacks on the Sentinel’s fire break, is still at the centre of a bitter row between the Hangberg community and various spheres of government – the City of Cape Town, the Western Cape Provincial Government and SA National Parks.

In the official view, Die Sloot is seen as a hotbed of drug and perlemoen smuggling, a fire hazard and an unhealthy place to live.

The City points out that many of the residents are in defiance of a court order which interdicts further settlement on this land, which is under the custodianship of SANParks.

Yet, in the absence of alternative housing opportunities in the area, occupiers like Jonkers say that they would sooner stay, risking arrest and evictions, than move from what they see as their ancestral home in Hangberg.

What’s more, Jonkers says, he built his shack in 2010. Only an eviction order, and not an interdict against settlement, can be used to evict him, he says.

For members of Hangberg’s community who identify as Khoikhoi, under the leadership of Chief Xam, Die Sloot represents the frontline in a fight for land “rightfully” belonging to the Cape’s earliest inhabitants.

Xam says Premier Helen Zille has been “obsessed with evicting Die Sloot’s people” for many years.

“We know why. It has a million dollar view across Hout Bay to Chapmans Peak. It is too good for poor people to enjoy that view. That is how they see us. But, our children are not moving. When the Boere (police) came for Santonio, there were children – six, seven, eight years old – on the street with stones in their hands at 3 am. The furthest that any one of us will move is to the graveyard of our ancestors at the foot of the hill.”

Xam’s threats of violent, even murderous, reaction to any further attempts by the police to arrest or evict occupiers from Die Sloot mirrors hardened community attitudes which led to resistance against the City evictions in September 2010. Over two days, Hangberg was locked down. Stones and petrol bombs from protesters were met by rubber bullets and tear gas from police – with each side blaming the other for escalating the violence. Sixty two people were arrested and eighteen were injured. At least three people lost an eye.

Chief Xam has warned of a renewed uprising in Hangberg if arrests and evictions continue at Die Sloot. Photo by Daneel Knoetze.

For resident Gregg Louw, the riots represented the climax of a systematic breakdown of relations between the community and local and provincial government. Both Louw and Xam were involved in establishing a Peace and Mediation Forum of 39 community representatives to negotiate a peace deal with the City in the riot’s aftermath.

Today, Louw is the PMF’s deputy chairman.

But, Louw says, the PMF and the Peace Accord’s appeal for “co-operation in good faith” has now been betrayed both by a “cynical” bloc in the community and by government actions.

After Jonkers was arrested, protesters attacked Louw’s block of flats – the privately owned Panorama – in Hangberg. Louw feared for his life and that of his family life as protesters surrounded Panorama, baying for his blood. Six of his neighbour’s cars were burnt out – leading Xam to reprimand the “youngsters” for not being prepared with enough petrol to burn down the entire building. Now, Louw says he will not attend a community meeting, declaring that he refuses to be verbally abused and become a scapegoat for the community’s anger.

Gregg Louw, vice-chairman of the Hangberg Peace and Mediation Forum, has accused both community “agitators” and government of subverting the peace accord signed in 2011. Photo by Daneel Knoetze.

Residents who feel left out of decision making should engage their 39 elected representatives, he says. Government he accuses of duplicity.

“As the PMF we do our best in the meetings and then we hear of special forces police raiding Die Sloot in the middle of the night without warning,” he says.

“Everyone, including the police and government knew that it was likely to cause a riot. And it did.

“They put our lives at risk. The community associate the PMF with the government because of the mediation process. I cannot sit with politicians anymore. They cannot be trusted, because they commit to peace here and they facilitate raid by a troop of armed police officers there.”

Xam and his supporters, on the other hand, have turned on the Forum – accusing it of “selling out”, of going rogue and striking deals without a popular mandate. The Peace Accord, and its blueprint for evacuating Die Sloot, are null and void, Xam says.

He says the community is told that Zille and Mayor Patricia de Lille are still meeting with the PMF, “but we never know what they are discussing”.

“There is no feedback, there is no discussion with the community.

“They can carry on eating biscuits with the fat cats. It makes no difference to us. But, if they then come to evict and arrest on the basis of some agreement that we do not condone, then the fires will burn high in Hangberg. It is easy to avoid this. All they have to do is come to community directly instead of sitting with people who have their own interests at heart.”

Roscoe Jacobs, secretary of the Hout Bay Civic Association which is not part of the PMF, also condemned last week’s arrest.

“Evictions and arrests are ongoing, but on dubious legal grounds,” he said, adding that some people, as Jonkers claims he did, built their shacks before the interim order against further settlement was handed down. Jonkers’ name, however, is excluded from a list of people who are “not” in contravention of the interdict against further settling.

A response to GroundUp from police spokesman Lieutenant Colonel Andrè Traut confirms that the arrest of Jonkers, for contempt of court, was planned for 2.30 am in an attempt to prevent an “altercation” with the community.

Louw wants to know whether provincial and municipal authorities knew about or helped to co-ordinate the police raid.

JP Smith, Mayco member for Safety and Security, said that the arrest for contempt of court was a matter between the Department of Justice and the police, and nothing to do with the City.

“It is not a political issue, so the City’s opinion on the matter is irrelevant,” he said.

But Mayoral Committee Member for Human Settlements, Siyabulela Mamkeli, has said that the riots were in response to the City’s action to remove an illegal structure.

In statements, both Mamkeli and Zille’s spokesman Michael Mpofu, government glossed over the apparent violence of the police’s night time raid and condemned the community’s reaction. Mpofu and Mamkeli said that government was fulfilling its obligations as laid out in the Peace Accord and listed a number of services, including a housing project, being rolled out in Hangberg. Die Sloot’s occupiers and their supporters were a “minority” who had waived their responsibility in terms of the accord, which has been made an order of the Western Cape High Court – specifically the evacuation of Die Sloot. The defiance was holding up Hangberg’s upgrades, Mpofu said.

But Xam, Jonkers and their supporters see themselves not as saboteurs, but as the community’s champions against a government that is distant and unresponsive, in spite of the Peace Accord. They say no new houses have been completed by the government in Hangberg since 1992. Nor has the new housing development been without its detractors.

Jonkers’ seven year old son, Liam Fortuin, saw his father stripped, beaten and pepper-sprayed in the family’s single bedroom shack at 2.30 am on September 30. He tried to interfere, but was pushed aside. When he cried out the police warned his mother to shut him up.

“He calls out for his daddy in his sleep,” says Liam’s mother, Jonkers’ partner, Tania Fortuin, who was recently discharged from hospital after a kidney removal.

“When he is awake, he talks about what he would do to the police - violent things. We have had to send him to stay with my mother in Mitchells Plain. Hangberg is no place for him at the moment.”

Jonkers’ mother, Fadwah Vardien, inspects the bedroom door that police broke down before assaulting and arresting her son. Photo by Daneel Knoetze.

Jonkers and Fortuin are in two minds about whether to return to their shack in Die Sloot. It is not the first time in recent months that the police have raided Die Sloot, and they fear that it will not be the last. Jonkers has opened a case of assault against the police officers at Hout Bay police station and the investigation has been referred to the Independent Police Investigative Directorate. Yet, he feels vulnerable.

“I know that this is not about enforcing the law, or the court order. The way they came at me was purely for intimidation. They didn’t evict me, because there was no eviction order. They simply beat me in the hope that I would decide not to come back. But, in honesty, I am afraid to return with my family. Next time, they may just kill me.”