22 July 2021

Illustration: Lisa Nelson

There is a growing narrative that blames South Africa’s slow vaccine rollout on supply shortages, especially of the one-shot Johnson and Johnson (J&J) vaccine. It is indeed frustrating that J&J have yet to commit to specific delivery dates for the 30 million doses ordered by the South African government. This obviously makes planning difficult. A more serious problem, however, is South Africa’s continuing failure to use the vaccines it has – including the J&J vaccine doses already in the country, and available for use.

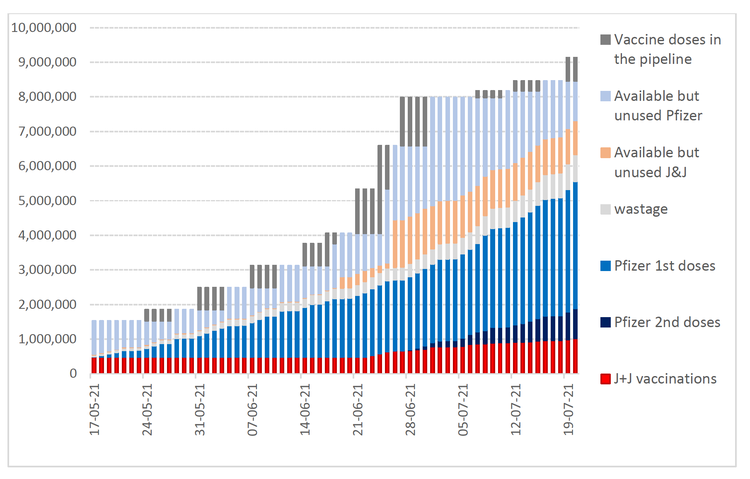

The graph shows the use of vaccines delivered to South Africa (using data from the national Department of Health). The red, dark blue and blue segments show the number of doses that have been used, on a cumulative day-by-day basis. The light grey section of each column shows estimated wastage. The orange and light blue sections show the number of doses that were available for use each day since the start of the rollout of the government’s programme on 17 May (taking into account time for delivery to vaccination sites). The dark grey sections at the top of each column show doses in the country that are not yet available for use.

South Africa has plenty of unused vaccine. This is clear from government information about vaccine deliveries and vaccination rates. As of 20 July, just over one million people had been vaccinated with the J&J vaccine (almost half of whom had been vaccinated in the earlier Sisonke trial, that is prior to the national rollout). This implies that there are almost one million (980,000) doses of the J&J vaccine sitting unused and available somewhere in South Africa. At the average pace of vaccination over the past two weeks, we could continue vaccinating for three months before running out of Johnson and Johnson vaccine.

It is likely that vaccinations have been proceeding faster than those reported on the EVDS system because of delays in reporting vaccinations. But even if we assume that the rollout of J&J vaccinations in workplace programs has been proceeding at more than double the reported speed, we still have at least one month’s supply of J&J vaccine in the country.

We clearly should be speeding up our vaccination rollout, and not taking refuge in the misleading “we are short of vaccine supply” argument.

The rollout of Pfizer vaccinations is much faster than for the J&J vaccine. Elderly people are coming back for their second doses whilst vaccination is in practice now open to anyone over the age of 35. People are queuing up for vaccination. About 650,000 vaccinations are being delivered per week. We currently have 1.1 million doses available, and Pfizer is expected to deliver two million additional doses this month [i.e. in July]. Clearly, the pace of vaccination can be accelerated.

In short, South Africa’s problem right now is not supply – it is delivery. Our workplace vaccination schemes appear to have been much slower than expected, though the vaccination of prisoners with the J&J should help boost numbers. We urgently need to find additional ways to reach large numbers of people, especially in the rural areas.

The government’s plan was to vaccinate most of the elderly population by the end of June and the entire adult population by early next year. This would require vaccinating fully an average of one million people per week. By 20 July, fewer than two million people had been fully vaccinated, i.e. with the single required dose of J&J or two doses of Pfizer. This includes the half-million health workers vaccinated through the Sisonke programme and only 1.4 million people fully vaccinated through the government’s programme since 17th May. Fewer than one million elderly people (i.e. less than 20% of the elderly population) have been fully vaccinated.

That’s right: The government’s plan requires vaccinating fully one million people per week but the government programme has fully vaccinated only 1.4 million people over more than nine weeks.

The government is currently vaccinating fully the equivalent of fewer than half a million people per week. At this speed, it will take until early 2023 to fully vaccinate the entire adult population, as the government originally promised would be done by early 2022.

When pressed, government officials and sympathetic commentators acknowledge that the rollout needs to accelerate. But they don’t appear to know how to achieve this.

One obstacle to the faster use of vaccines is that they are not where they need to be. Unfortunately, the national Department of Health (NDoH) is tight-lipped on how vaccines are allocated between the various “pipelines”: The “public sector” (meaning the provincial health departments and the sites under their direct control), the “private sector” (meaning primarily the private hospital and pharmacy chains) and “occupational groupings” (such as the South African Police Services and some private companies).

Dr Crisp has repeatedly declined to tell us how vaccines are allocated, despite this data being readily available (he himself says) on the NDoH Stock Visibility System. The co-ordinator of the private sector operation - Stavrou Nicolaou, a senior executive at Aspen Pharmacare, South Africa’s leading vaccine manufacturer, has also declined to tell us how vaccines are allocated within the private sector.

We cannot help but wonder why there is so much secrecy over this. What are they hiding?

The Limpopo provincial department of health has been praised for its effective rollout programme. We are impressed also by the rollout in the Western Cape (where the provincial department of health is far ahead of the NDoH in terms of transparency and public information).

Without good data on where vaccines are sitting unused, civil society cannot begin to hold to account either the provincial health departments or the private sector players that are underperforming. Perhaps this is why the NDoH and Nicolaou do not want to say where the unused vaccines are piling up.

Without more data we also cannot tell just how inequitable the vaccination rollout has been. Kate Alexander and Bongani Xezwi suggest that the rollout has been inequitable, failing to reach many of the elderly people who are most vulnerable to Covid-19. But the NDoH is not making available sufficient data for civil society to assess who is and who is not being vaccinated and we doubt that the NDoH has sufficient capacity to analyse their data “in house”.

The relaxation of the government’s “prioritisation” plan is a mixed blessing. Yes, opening vaccination up to young people means that more people will be vaccinated quickly. But the risk is that the rising pace of vaccination obscures the fact that the less than one half of the over-60 population has received a single dose of Pfizer and only 10% have received both doses. In our enthusiasm to vaccinate as many people as possible we must not overlook the fact that the people who really need protection against Covid may be left behind.

Views expressed are not necessarily those of GroundUp