4 August 2021

A stretch of N2 highway, alongside the border of eSwatini, near where a police officer abducted and raped a 17-year-old schoolgirl in June 2014. Photo: Annelia Smit

Policemen have been accused of nearly 1,000 rapes since 2012. Many of them abused the authority of their positions to aid them in these crimes, a new investigation by Viewfinder has found. Yet, police management rarely disciplines or dismisses the officers involved.

On the afternoon of 6 June 2014, 36-year-old Ermelo police Warrant Officer Sipho (name changed) was sitting alone in a white bakkie on a quiet stretch of the N2 highway in south-eastern Mpumalanga. Through his windshield, Sipho spotted 17-year-old schoolgirl Lerato (name changed) walking towards him.

The details of what happened next were later captured in Lerato’s statement to investigators. She was there to catch a taxi home, as she usually did on Fridays after school, she said. Sipho leaned on his hooter to catch her attention. At first she ignored him. When she eventually looked up, Sipho was standing next to the car. He was wearing a uniform: blue pants and a blue shirt, with a police jersey pulled over it. There was a blue light on the bakkie’s dashboard, she recalled.

Sipho said Lerato walked over and informed her that she was under arrest on suspicion of being an illegal immigrant from Swaziland - the border was within a short distance from the road. He ordered her into the front seat. Frightened, not knowing what to do, she obliged.

Warrant Officer Sipho then drove off with the teenager. He pulled off to a gravel road beside the highway.

“He told me he is taking me to Johannesburg, where I would be raped by more than 15 African males. And, (he) got out and opened my door. He then grabbed my legs and pulled them towards the side where he was standing. He then told me to undress and I refused… I tried to resist, but he told me that he would assault me,” Lerato told investigators.

Sipho then raped her.

Afterwards, Sipho drove Lerato back to the spot where he had abducted her. He made small talk - telling her that his shift was over and that he was headed to Durban. Lerato’s taxi fare of R30 and cellphone had fallen from her pockets during the rape. He gave these to her, and then he drove off.

Lerato used her cellphone to record the police bakkie’s licence plate number. In tears, she sent a “please call me” to her older brother. He called back and instructed her to catch a lift to a police station to report the case, which she did.

Three days later, Sipho’s police colleagues arrested and detained him at Piet Retief police station. On the fourth day, Lerato came face-to-face with her rapist once again. This time, she walked up to pick him out of an identity parade. A little over a year later, Sipho was convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison. The magistrate ordered that he be placed on the National Register of Sex Offenders.

A check with the Department of Correctional Services’ (DCS) spokesperson Singabakho Nxumalo established that Sipho spent only three nights in prison before he was released on bail, pending an appeal. Neither the DCS nor the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) in Mpumalanga could say whether the appeal was successful. But, it appeared that Sipho never returned to prison, Nxumalo said.

In South Africa, police officers are accused of thousands of violent crimes every year. Among them, rape and sexual assaults account for some of the most serious and opportunistic abuses of power by police in the country. And, Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) data suggests that they routinely get away with it.

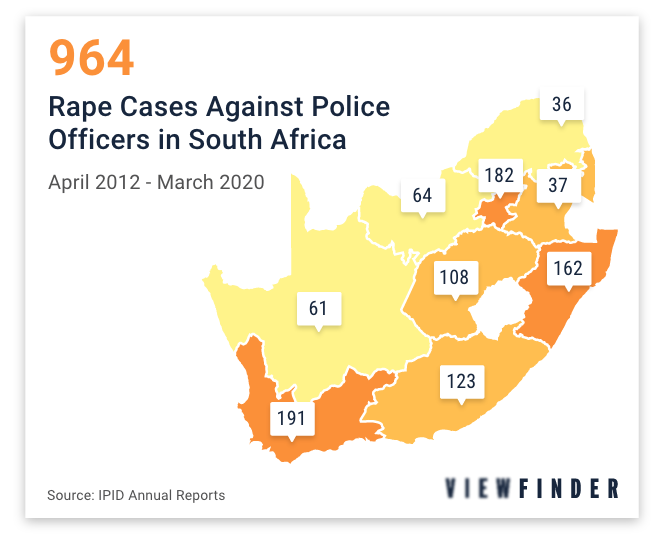

Since 2012, IPID has registered nearly a thousand rape cases against on- and off-duty police officers. More than a third of these are against police officers who were “on-duty” at the time that they apparently committed their crimes.

With each case that IPID registers, a complaint description is taken down, usually from the statements of people who say they experienced abuses by police officers. From the database, Viewfinder isolated 220 rape complaints registered against “on-duty” police officers across the country between April 2015 and March 2020 - the most recent five-year period for which audited data is available. These descriptions consistently pointed to cases where police officers stand accused of abusing the power, trust or privilege of their position in order to commit rape - as Warrant Officer Sipho did when he abducted and raped Lerato.

In 38 of the complaints in Viewfinder’s sample, women said that they were raped while in custody or under arrest. In 26 of the cases, the victim of an alleged rape was a minor. In some of the descriptions, patrolling on-duty police officers reportedly rolled up to women walking alone on the streets at night. They offered to give these women lifts home, but instead drove to secluded areas to rape them.

A previous Viewfinder article highlighted the case of police officers accused of gang raping a woman who had called on them for protection from an abusive partner in northern KwaZulu-Natal. Viewfinder’s sample has now revealed 14 other examples of officers accused of raping women and girls who had called on the police or been entrusted to them for help.

In January 2017, a police officer from Zamdela in the Free State visited a domestic abuse survivor to see how she was “coping” after the arrest of her husband. He ended up overpowering and raping her on her bed, the woman later reported to IPID.

In August 2016, a 55-year-old Warrant Officer was accused of raping a 15-year-old girl inside the trauma room of Montagu police station, in the Western Cape. The complaint does not expand on why the girl was there, but police station trauma rooms are designated safe spaces for people who have experienced violence or other traumatic events.

In September 2016, two patrolling police officers offered a student walking in the Cape Town city centre late at night a lift back to her residence. Instead, according to IPID’s complaint description, they drove her to an “unknown” location and raped her. The woman eventually refused to pursue the case and the file was closed, IPID reported.

IPID has registered 964 rape cases against both off- and on-duty police officers in South Africa since 2012.

With a total of 73 cases, IPID’s Western Cape office registered the highest number of rape cases against “on duty” police officers in the country, between 2012 and 2020, (the latest years for which audited figures are available). Thabo Leholo, IPID’s head in the province, said that the abuse of power is the common thread that runs through these rape cases as well. Though alleged rapes account for a small fraction of IPID’s case load, compared to the hundreds of police assaults registered annually in the Western Cape for instance, Leholo says that these cases are prioritised and assigned to the most experienced case workers on his team.

“Yes, some of these rape cases derive from opportunism, because of the power that the police have and the abuse that they are able to mete out against the powerless - people who are in their custody or people who have come to them,” said Leholo.

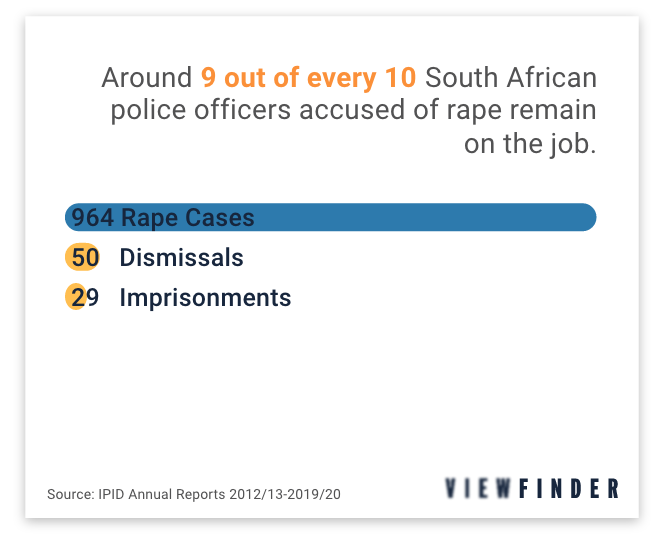

The watchdog’s data suggests that - in spite of its “prioritisation” of rape investigations - as many as 97% of police officers investigated for rape are not convicted in court and imprisoned.

One reason for the low rates of criminal convictions, said Leholo, is delays in technical reports which are needed before dockets can be successfully prosecuted. These delays affect the criminal justice system as a whole. Earlier this year, police minister Bheki Cele announced a backlog at the country’s Forensic Sciences Laboratories of more than 200,000 cases. More than 77,000 of these were gender-based violence and femicide cases that were otherwise ready for court.

But these delays need not mean that police officers implicated in these crimes must remain “on duty”. The South African Police Service (SAPS) discipline regulations define rape as a form of serious misconduct and empower the police to suspend and dismiss officers following disciplinary proceedings. The burden of proof for obtaining a conviction in these proceedings is considerably lower than in criminal courts.

Yet, for the 964 rape cases registered against police officers between April 2012 and March 2020, SAPS only dismissed 50 officers for rape.

Very few police officers accused of rape actually face imprisonment or dismissal.

Earlier this year, IPID pointed out to Parliament that there was widespread disregard within SAPS for its findings and recommendations against police officers implicated in violent crimes. Though SAPS is legally obliged to initiate departmental proceedings against police officers recommended for discipline, IPID reported that this did not happen in over half of the disciplinary recommendations cases forwarded to the police in 2020/21. In the case of rape, only three of 30 recommendations led to SAPS convicting officers in disciplinary hearings at the close of the financial year.

Though IPID’s investigation of Sipho’s actions led to a court conviction, it appears that it did not result in internal disciplinary action against him. A month after he was accused of raping Lerato, IPID recommended to the police that disciplinary proceedings be initiated. According to IPID, SAPS reported back that it had initiated an “investigation”. Then, silence. IPID did not report any further progress in the disciplinary process. Right up to the moment when he was convicted and sentenced to prison, the status of the recommendation was stalled at: “awaiting response”.

In response to queries this week, Mpumalanga SAPS spokesperson Colonel Donald Mdhluli declined to comment, saying that discipline was a “private matter” between the employer and the employee.

The real name of Sipho, the police officer, cannot be used for legal reasons. The real name of Lerato, the rape survivor, has been withheld at her request.