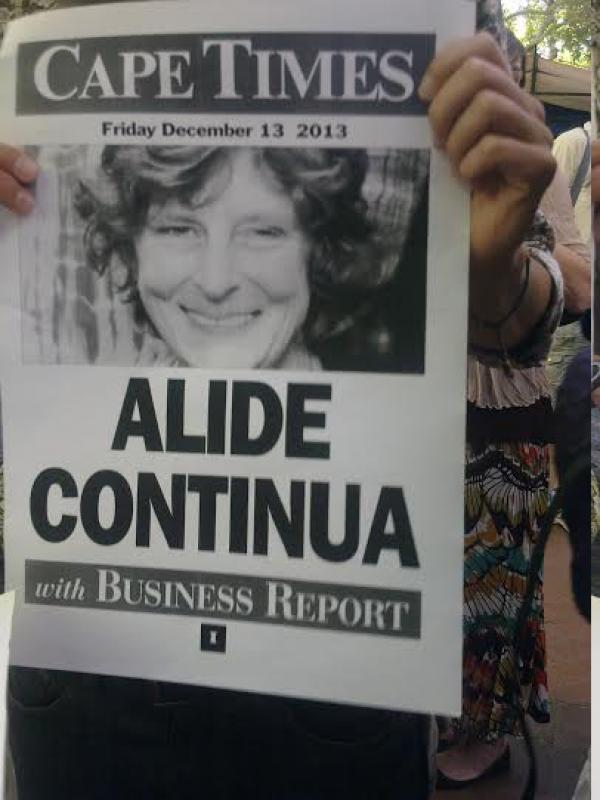

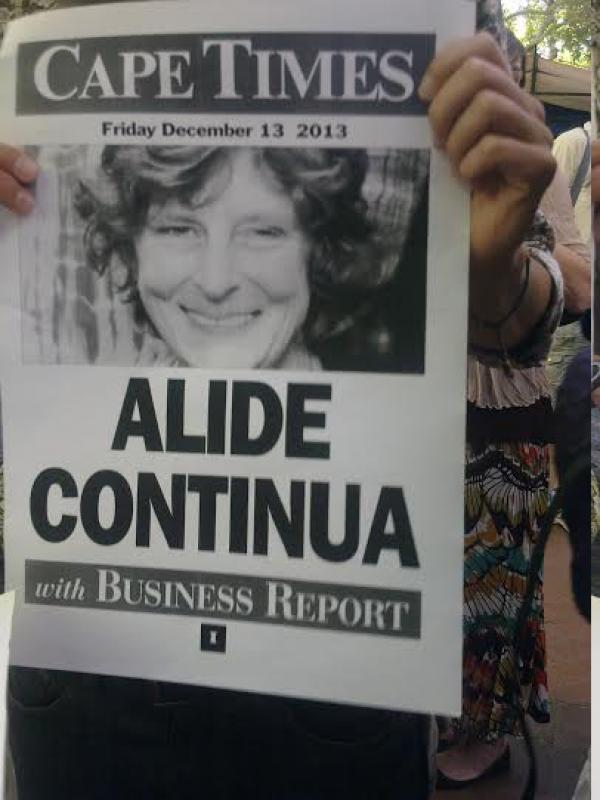

Placard used by protesters at picket outside Cape Town earlier this month.

29 December 2013

A lack of adequate resources and asset-stripping by the Irish carpetbagger Tony — now Sir Anthony — O’Reilly are the real problems with the Cape Times, not the undeniable quality, let alone pigmentation, of the staff. But there are other issues too that require examination.

What interest or standing does Andre Kriel, general secretary of the clothing and textile workers’ union (Sactwu) have in the ongoing dispute involving the Cape Times and Independent News Media (INM)? This question has become pertinent since Kriel, as early as December 14, demanded that all correspondence regarding the dispute “should be via me”.

According to Kriel, he had spoken to the putative owner of INM, Iqbal Surve, and that Surve had agreed that he, Kriel, should “facilitate this matter”. Kriel has also launched attacks on the Cape Times, claiming that this newspaper “has not ever carried one positive story about the great struggles that workers have waged”. He clearly sees his role as one campaigning against “neo-liberalism”, something he apparently sees as epitomised by the Cape Times.

However, Iqbal Surve, the executive he admits to serving, has stated that one of the problems with the Cape Times under its now effectively sacked editor, Alide Dasnois, was that the newspaper was “not business-friendly enough”. In fact, one of the proposals of the new management is to remove trade union and other labour/worker news to separate publications, presumably financed, at least in part, by the labour movement. This would be a journalistic travesty since newspapers should attempt to reflect all of society and not be forced to cater for ghetto interests.

The simple fact is that any newspaper worthy of the name attempts to provide a reasonable reflection of the society in which it functions. It also provides a forum where different points of view may be aired on opinion and letters pages. In this regard, the Cape Times has, certainly in recent years, been as good as any and perhaps better than most, despite a paucity of resources. Kriel’s caricature of the newspaper therefore reveals that he has little or no knowledge of the role of newspapers in general, of journalism or, specifically, the situation of, and the items carried in, the Cape Times.

But why he should be so interested in this matter is a question that continues to be asked. Is it because Sactwu, through its investment company, has pumped a few hundred million rand into the Sekunjalo-led consortium that now controls INM? After all Sactwu now owns the Seardel clothing factory where Kriel has promised the 3 000 workers “jobs for life”.

However, his intervention — whatever motivates it — is essentially a sideshow. The real issue is the facts at stake as a rag-tag group of critics continues to assault what is, in effect, the straw man of the Cape Times. I don’t think anyone knowledgable — and not least the journalists working on that title — would deny that journalistic standards have slipped over the years. That they were able to be maintained at the present level is an incredible tribute to those who produce the newspaper (as well as other INM titles). Take this simple fact into account: twenty years ago there were roughly 5,000 INM employees. Today the number is roughly 1,500.

The company was bought in 1994 by baked beans tycoon, Tony — since 2001 Sir Anthony — O’Reilly, reputed to be Ireland’s first billionaire. He set about syphoning profits off to pay fat dividends and to shore up the losses of his newspapers in England and Ireland. Then began the asset stripping of the once sound Argus company. O’Reilly’s initial investment of R725 million resulted in billions of rands in profits flowing abroad.

In ten years to 2010, for example, it is estimated that some R4 billion moved offshore. At the same time, there was no investment locally in staffing or machinery and, when worker levels were cut as far as they could go, physical assets were sold off. In what I called at the time an “act of gross vandalism”, the country’s oldest newspaper clippings library was thrown out. The librarians who worked there were also retrenched.

Yet O’Reilly continued to press editors to increase profits while failing to provide any investment — and appeals by editors and senior staff were ignored. In 2000, this asset-stripping pirate who had been welcomed by Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela as an investor, was appointed a member of Thabo Mbeki’s International Investment Council. In what now looks like something of a sick joke, this IIC was set up to advise government on how to attract foreign investment.

But O’Reilly did not interfere in editorial matters. He was clearly interested only in the money. What this meant was that journalists in particular, had to cope with massively increased workloads and had, increasingly, to rely on trainees and interns while management continued to raise cover prices. Standards fell and, along with them, circulations among an increasingly price-conscious pubic.

Some facts to consider:

the Cape Times and Argus and other titles no longer own Newspaper House. It was sold. And these newspapers are no longer printed by the company: that job is now outsourced.

Outsourced too is the printing of the biggest metropolitan daily in the country, the Johannesburg Star (and related publications).

All of this has very little — if anything — to do with levels of labour or any other coverage or the pigmentation of journalists. When a newspaper has too few skilled staff, it is obvious that there will be greater reliance on those sources that readily provide comment. In such an environment it is little wonder that there are, in South Africa, now more public relations or communication consultants than journalists. The issues of investment, staffing levels and training are what should be addressed, along with that of ownership and, crucially, editorial independence that cannot really exist outside of a properly resourced media where all operations are transparent.