25 January 2021

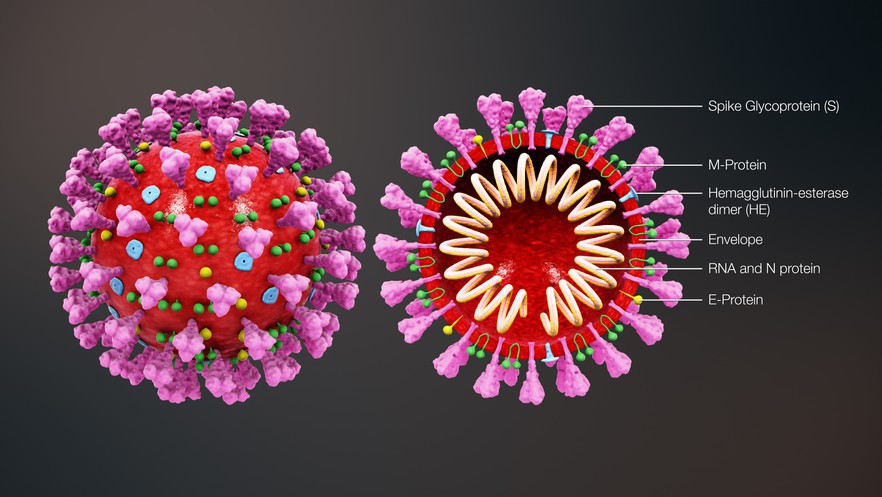

Structure of coronavirus. Image by Scientific Animations via Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Researchers from South Africa’s National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) have published a study suggesting that people who previously tested positive to Covid-19 may not be immune to the new variant of the virus 501Y.V2, currently sweeping the country. This may also have implications for the efficacy of vaccines developed using earlier strains of the virus.

Coronaviruses have sharp bumps that protrude from their surface known as spike proteins. As these spikes appear like a crown (corona is Latin for crown), spike proteins are what give coronaviruses their name. 501Y.V2 differs from earlier forms of the virus in terms of mutations in its spike proteins.

Spike proteins are important in the acquired immune response as the body uses them to recognise a coronavirus, and then produces what are called antibodies, specific to it, to neutralize its effects. So the crucial question is whether antibodies raised by earlier forms, or vaccines based on the spike proteins, can deal effectively with the new variant.

The study (which is not yet peer-reviewed) examined the blood of 44 people who had recovered from Covid-19 to probe the capacity of their antibodies to neutralize 501Y.V2 in laboratory tests. To do this they used a pseudovirus — a virus modified for experimental purposes — that infects cells using spike proteins.

They showed that 501Y.V2 mutations blunt the effects of neutralizing antibodies that recognize a key region of spike protein. By contrast, pseudoviruses with the full suite of new mutations associated with 501Y.V2 were fully resistant to convalescent serum from almost half of the 44 participants, and were partly resistant to the sera of most of this sample. (Convalescent serum is blood filtered of some of its cells, taken from people who have recovered from Covid-19.)

There are now anecdotal reports of reinfections with 501Y.V2 in South Africa, so it seems possible that the variant’s dominance in the second Covid-19 wave over the past two months could be driven, at least in part, by its capacity to evade immune responses that developed in response to earlier versions of the virus. But, so far, analyses from NICD don’t support this, according to Penny Moore, who led the study. (The increased transmissibility of the new variant has also contributed to its rapid spread).

The study is one of several which emerged last week which have tried to address similar questions about immune responses to other new Covid variants which have evolved in Brazil, the UK and the US. All have probed antibodies’ capacity to neutralize these variants in laboratory tests, but not the wider effects of other components of immune response.

In addition to acquired immune responses, humans have an innate immune response which may be unaffected by spike protein mutations, but which may play a crucial role in responding to Covid.

Neither do these studies show that changes in antibody activity necessarily make any difference to the effectiveness of vaccines or the likelihood of reinfection. The team will soon test 501Y.V2 with serum from participants in vaccine trials.

First author on the study is Constantinos Kurt Wibmer, who holds a prestigious Future Leaders African Independent Research (FLAIR) Fellowship from the Royal Society and the African Academy of Sciences. This scheme is enabling young sub-Saharan African scientists to do cutting-edge research, of which this is an example.