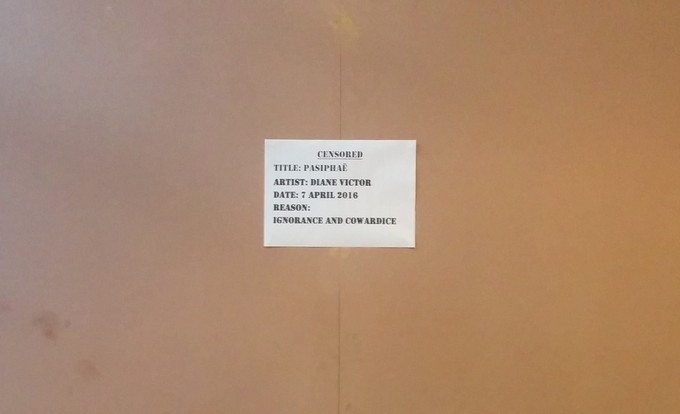

Last week UCT covered up Diane Victor’s artwork in Molly Blackburn Hall. Shortly afterwards, this pamphlet appeared on it. Photo: Nathan Geffen

14 April 2016

These are tough times for art at UCT.

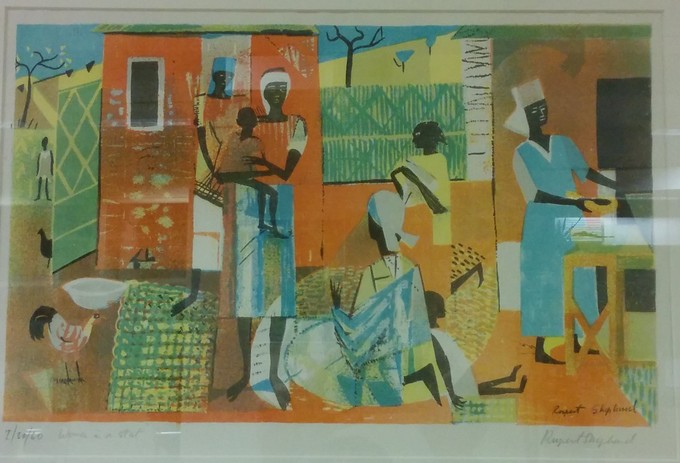

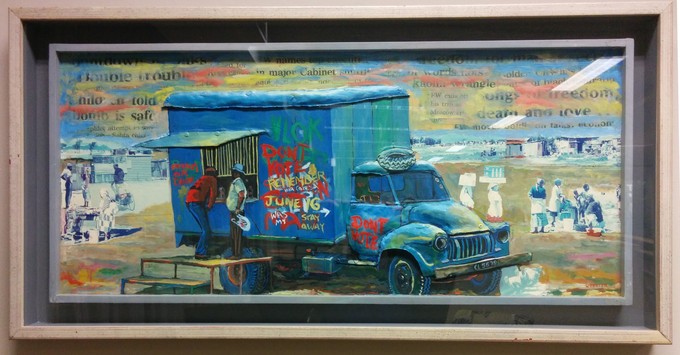

Paintings were burnt in a protest in January. An exhibition in Molly Blackburn Hall of events in 2015 was taken down when some students disapproved of it. In the past couple of weeks GroundUp has reported that over 70 works have been taken down or covered up by the Works of Art Committee and the Artworks Task Team - the latter established by the university council in September. These include Willie Bester’s Saartjie Baartman and Breyten Breytenbach’s Hovering Dog, as well as works by Zwelethu Mthethwa, William Kentridge and Stanley Pinker.

In the 1930s Diego Rivera, a Mexican communist, friend for a while of the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, lover of Frida Kahlo, and one of the great artists of the 20th century, was commissioned to paint a fresco titled Man at the Crossroads in New York’s Rockefeller Centre. Before it was complete, Nelson Rockefeller ordered its destruction.

Here is Rivera’s recreated version of it called Man, Controller of the Universe:

A careful look at the figure to the right of centre shows the reason why Rockefeller went apoplectic when he saw it. It’s Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Bolshevik revolution.

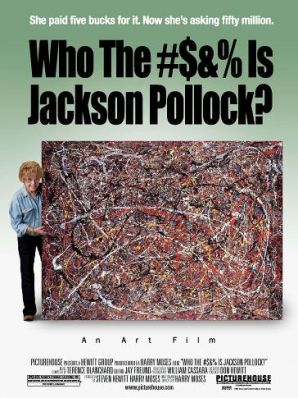

The 1999 movie Cradle will Rock shows Rockefeller, played by John Cusack, deciding after this incident to invest in art that wouldn’t upset. Hence, the movie suggests, the rise of inoffensive abstract art. It is an interesting take of how artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko became so popular.

Institutions of learning, such as UCT, should try to do a little better than petulant capitalists like Rockefeller.

Artworks are put up, taken down, replaced, refurbished and removed all the time. For the most part, few people, notice or wonder about the process by which this is done. The art displayed at UCT, much like the curricula of, say, philosophy or computer science, is determined by experts. Usually this makes sense. Most of us, including me, don’t know enough about art to make sensible decisions.

But what the Artworks Task Team is doing is not the normal work of curation. It is not replacing art with the aim of refreshing displays. It is not trying to enhance UCT’s art collection. It is not acting to challenge students, to make them question their views and prejudices. On the contrary: it is removing art and acting out of fear that particular artworks offend or will be destroyed.

UCT’s vice-chancellor Max Price has published a statement explaining the purpose of the Artworks Task Team and the continued covering up and taking down of art that is deemed offensive for “cultural, religious or political reasons”.

Price gives examples of what he calls “problematic curatorial issues” including:

These criteria are so wide-ranging that almost any painting or sculpture could fall foul of them, especially given how varied and personal responses to art are.

And the primary target of the Artworks Task Team has been the centre of academic life and learning at UCT: the main library and the adjoining Molly Blackburn Hall. It is here that nearly all the publicised acts of removal and covering have taken place. Under no reasonable interpretation can this space be described as perpetuating colonial or racist ideas. Interpretation of art is subjective but there’s a limit to the reasonableness of subjectivity. (There are areas which look like colonial relics on campus: Smuts Hall for example. But the library is not such a place.)

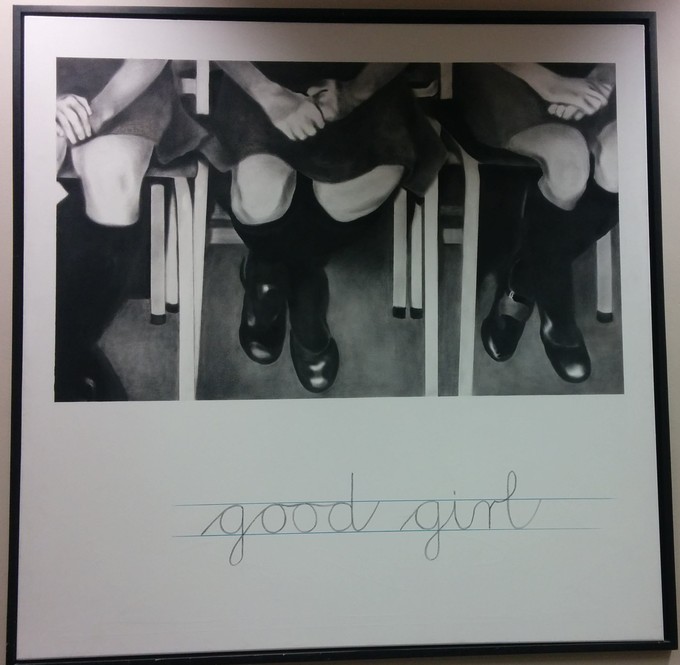

The art in the library clearly has been selected with care, with the intention of being stimulating, aesthetically and politically. What is being removed or covered up is art with sexual connotations. It is puritanism as much as anti-racism that appears to be determining what is culled.

Price, in this instance, has done the opposite of what needs to be done. In a time of unprecedented public interest in UCT’s cultural artefacts, instead of retreating in response to Rhodes Must Fall’s (RMF) criticisms and actions, he should take the opportunity to increase debate and discussion on campus.

Price and UCT’s council should call public meetings in the Leslie Building, Jameson Hall and the library to discuss and debate art (and building names like Jameson Hall) on campus. These meetings would need strong chairs. RMF, artists, liberals, socialists, conservatives, theists and atheists should present their views and question each other. Students should hear the contrasting views of Ramabina Mahapa, Breyten Breytenbach, Diane Victor, and Malcolm Payne.

Council should be encouraging debate and civil disagreement (not merely by inviting email correspondence), just as, to some extent, happened before the Rhodes statue came down. It should call for more artworks. It might consider issuing a challenge for depictions of the events on campus last year, and other imaginative ideas. It should encourage art to flourish, not be covered up or removed. It should have done this months, if not years ago. It’s still not too late.

Over the past year Price and members of the council have been insulted and condemned by RMF, black and white alumni, unions and academics and some newspapers, often unfairly. Price has been pelted with bottles and his office has been firebombed.

Price’s letter seems a consequence of being under constant siege, and believing that the university generally is under siege.

But it isn’t. If you walk down the main avenue of upper campus on a sunny afternoon, you find thousands of students, black and white – often together – doing what students do: dancing in the Molly Blackburn hall, studying in the library, sitting in groups on the plaza chatting, sometimes discussing politics or science, fretting over tests, loans and money, often holding hands and sometimes kissing. UCT is a vibrant place.

I am confident UCT can deal with open debate about its art and cultural monuments. Sure, there will be conflict and anger; and the outcomes of the debate aren’t knowable in advance. But UCT might also emerge a better institution for it. I wish the besieged administration could see this, because its current approach suggests it has a low view of the institution.

Correction: The initial version of the article stated that UCT’s council supported Max Price’s letter. This is apparently incorrect and the article has therefore been updated.

Post-publication update: It was noted that the Works of Art Committee and the Artworks Task Team have together taken down over 70 artworks, and a link was added to the document that confirms this.

Geffen is GroundUp editor and a post-graduate student at UCT. Views are not necessarily those of other GroundUp staff.